NATALIE ZEMON DAVIS

“Two negroes hanged,” John Gabriel Stedman wrote in his Suriname journal for March 9, 1776, and then two days later, among his purchases of“soap, wine, tobacco, [and] rum” and his dinners with an elderly widow, he records, “A negro’s foot cut off.”1 Stedman expanded on these events in the later Narrative of his years as a Dutch–Scottish soldier fighting against the Suriname Maroons: And now, this being the period of the [court] sessions, another Negro’s leg was cut off for sculking from a task to which he was unable, while two more were condemned to be hang’d for running away altogether. The heroic behavior of one of these men deserves particularly to be quotted, he beg’d only to be heard for a few moments, which, being granted, he proceeded thus––

“I was born in Africa, where defending my prince during an engagement, I was made a captive, and sold for a slave by my own countrimen. One of your countrimen, who is now to be my judge, became then my purchaser, in whose service I was treated so cruelly by his overseer that I deserted and joined the rebels in the woods . . .”

To which his former master, who as he observed was now one of his judges, made the following laconick reply, “Rascal, that is not what we want to know. But the torture this moment shall make you confess crimes as black as yourself, as well as those of your hateful accomplices.” To which the Negroe, who now swel’d in every vain with rage [replied, holding up his hands], “Massera, the verry tigers have trembled for these hands . . .and dare you think to threaten me with your wretched instrument? No, despise the greatest tortures you can now invent, as much as I do the pitiful wrech who is going to inflict them.” Saying which, he threw himself down on the rack, where amidst the most excruci ating tortures he remained with a smile and without they were able to make him utter a syllable. Nor did he ever speak again till he ended his unhappy days at the gallows.2

Stedman’s heroic runaway slave is given the sentimental expression so appreciated by English readers of his day, including an elevated translation of the lively Creole (Neger Engelsche, or Sranan as it is now called) that the African would actually have spoken before his judges.3 But Stedman did witness the event (he visited the man with the mutilated limb a few days later4) and his account includes some of the features of criminal justice that would be important for Suriname slaves in the eighteenth century: the link between judges and slave owners, the use of an extreme form of torture, the imposition of the death penalty for running away, and the memory of Africa.

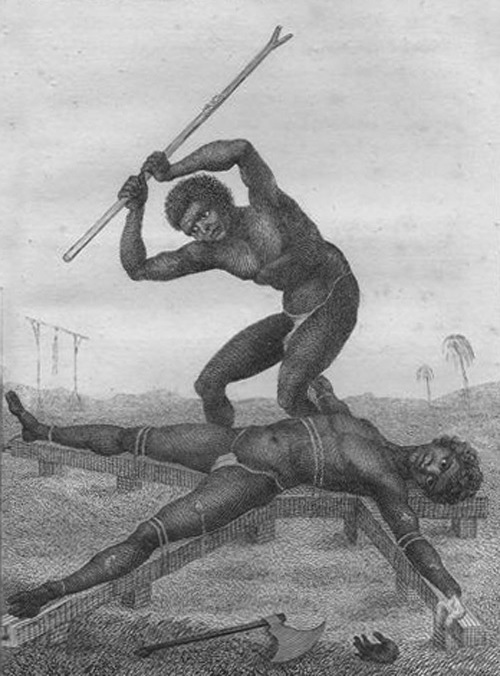

Figure 1. A runaway slave being executed on

the rack in 1776. Source: John Gabriel

Stedman, Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition

against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam

(London: J. Johnson, 1796), vol. 2, facing

p. 296.

In this article I describe the varieties of criminal justice experienced by slaves in Suriname in the late seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries, both those endured under their masters and the colonial government, and that which they created themselves on their plantations. I am addressing here certain gaps in the history of slavery in those centuries and also in the history of criminal law and prosecution. Studies of slavery in the Americas and the Caribbean, immensely rich as they have been, have described the disciplinary regimes on plantations and the harsh punishments meted out for revolt.5 The various law codes governing the status of slaves, their conduct, and the conduct of their owners toward them have been examined, Elsa Goveia’s West Indian Slave Laws of the 18th Century (1970) being the pioneering venture.6 But the whole cluster of activities considered as “crime” in regard to slavery, their detection, and their punishment—including the slaves’ own efforts at policing—have been little treated as such. Therefore, my intention in “Judges, Masters, Diviners” is to expand for Suriname the paths opened by Philip J. Schwarz in regard to slaves and the criminal law in Virginia; by Mindie Lazarus-Black in regard to slave laws, slave courts, and slave resistance in Antigua and elsewhere in the British Caribbean; and by Diana Paton in regard to the affirmation of masters’ power in the slave courts of Jamaica.7 As for the African past, innovative studies have unearthed continuities from or transformations of African beliefs and practices in the realms of slave healing, religion, and agriculture.8 I will go on here to suggest possible carry-overs or creolization in detecting, judging and punishing crime. Memory will play a role in my account: memories from the African societies from which slaves had been wrenched and memories of slave experience bequeathed to future generations.

Historians of European criminal law and prosecution have rarely made the crime and punishment of slaves in the colonies part of their story, even though most settlers and plantation owners and their law codes were European. Studies of the early modern Netherlands have taught us much about the experience of working people and the poor in the criminal courts there and about the reform of criminal law and public execution in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, but have not extended themselves to comparison with the busy Dutch slave world.9 Cross-cultural reviews of colonial law tend to pick up the account in the nineteenth century where the “creating a docile, disciplined labor force” by imperial governments is discussed primarily in terms of “groups released from the control of masters, owners or chiefs.” With a longer historical perspective, Lauren Benton has incorporated polities with slave systems into her Law and Colonial Cultures, and they add much to her analysis of “legal pluralism.” 10 I hope “Judges, Masters, Diviners” will provide an example helpful for her approach and also suggest further ways to think about relations between the practice of criminal law in the slave colonies and in Europe during the early modern period.

Founded initially as an English settlement, Suriname had passed to the Dutch after the 1667 Treaty of Breda and was eventually owned by the chartered Society of Suriname, the Society’s shares being divided between the West India Company, the city of Amsterdam, and the well-born Sommelsdijck family. Under the sovereignty of the States-General, the “exalted” Directors of the Society oversaw the colony’s activities from the Netherlands, appointing the governor and sending him directives on the Dutch boats that plied the Atlantic during the sailing season.11

Around 1700, some 700 people of European origin were living in the town of Paramaribo and the plantations along the Suriname, Commewijne, and Cottica Rivers: Dutch, Portuguese Jews, Huguenots from France and the Netherlands and other places where they had taken refuge after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and English men and women who stayed on from the initial settlement. Some 8,500 people from Africa were producing sugar as slaves on the plantations, and already, approximately 1,000 more Africans had escaped to the rain forests to live as Maroons, sharing that space with indigenous Caribs, Arawaks and Wayanas.

By the 1780s, the European population had increased to approximately 2,000–3,000 persons, with Swedes, Germans, and Swiss added to the mix and with Portuguese and German Jews representing approximately a third of the settlers. To the sugar so arduously produced on the plantations had been added coffee, chocolate, cotton, and timber. The slave population raising these crops had multiplied sixfold to more than 50,000 people, and now some 5,000 Maroons were living in forest villages, divided into three tribes with their own kings and headmen.12

Although the word “criolo”—that is, born locally—was appearing more often next to a slave’s name on the plantation inventories after the middle of the eighteenth century, the majority of slaves were still born in Africa. From 1730 to 1780, more than 124,000 persons were transported to Suriname on the slave boats.13 Some had been brought up in the Central African kingdoms in Angola and the Kongo, where the Bantu Kikongo languages were spoken, others in the Akan and Asante kingdoms of the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana). Many more had come from the Slave Coast, that is, from the polities of the Gbe-speaking peoples along the Bight of Benin (in present-day Benin, Togo), such as the coastal kingdoms of Arda and Hueda and the powerful inland kingdom of Dahomey. Others yet were Yoruba-speakers from the ancient kingdom of Oyo and elsewhere west of the Niger River. Although some children were on board and survived the Middle Passage, most of the people crammed into the slave decks were in the preferred age range of fifteen to thirty-five.14

Let us first consider the notions of crime, its detection, and its punishment, which these Africans brought with them to Suriname—as well as we can know them from late seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sojourners and slavers among the farmers, merchants, fishermen, and warriors of the coastal kingdoms of west Africa. Our sources will be the memoirs and accounts of men such as Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, Capuchin missionary to the kingdoms of Kongo and Angola in the mid-seventeenth century; Willem Bosman, factor for the Dutch West India Company on the Gold and Slave Coasts for fourteen years in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, and Ludewig Ferdinand Rømer, factor for the Danish West India and Guinea Company on the Gold Coast in the 1740s; William Snelgrave, who began as a young sailor on his father’s slaver in 1704 and then captained his own English slave boat on into the 1730s, and the surgeon John Atkins, who served on an English slave ship in the early 1720s; Olaudah Equiano, who lived as a boy among Igbo-speaking villagers in what is now southeastern Nigeria in the late 1740s and early 1750s until he was kidnapped and forced to endure the Middle Passage as a slave; and the Moravian Brother Christian Oldendorp, who in the late 1760s interviewed slaves on Saint Croix and other Danish islands about their African past.15

The actions named as “crimes” were murder, poisoning, witchcraft, theft, adultery (a serious crime in these polygynous societies), kidnapping, and major physical injury. “Trivial crimes” included beating someone, especially a young man beating another, and reviling another person, a troubling act in kingdoms where mutual deference and politeness were required in even a brief encounter. In some places lying could be punished as an offense.16

Along the whole range of the Guinea Coast and inland kingdoms, the gods were always drawn upon for divination and detection—not the high god who ruled more distantly over all, but one of the pantheon of responsive lesser gods, the voudun or orisha, who ruled realms of the sea or the air, were embodied in a special kind of tree or snake, or were more intimately connected to an ancestral spirit. The diviner’s rod or “fetish” as the Europeans called it, encapsulated the god’s presence, often a wooden rod filled with earth, oil, bones, feathers, hair, or other objects imbued with divine aura.

Seers/diviners were called in at the earliest stages of crime detection, including when the victim and others were unsure who had been the perpetrator. An Akan diviner could conjure the power of a god into some food or drink and leave it in place where it would entrap a thief whose identity was unknown. Death was usually assumed to be “unnatural,” that is, to have a source in some human or divine agency, and the dead person was asked to assist in uncovering it. To catch an unknown poisoner, as Olaudah Equiano remembered from his Igbo village, the diviner ordered the corpse to be carried toward the grave, whereupon instantly the bearers were compelled to run to a house in which the poisoner lived. In upper Guinea, among the Mende and Temne peoples of the Sierra Leone region, the bearers questioned the corpse about a possible witch or poisoner responsible for his or her death and were impelled toward a special bough if they hit upon a suspicious name.17 Meanwhile in the kingdom of Akim along the Gold Coast, an accuser alerted the village drummer to assemble the inhabitants and made his or her charge in public.18

Once accused of a crime—for example, theft, murder, adultery, poisoning, kidnapping—a person who wanted to establish his or her innocence had to go through a test with the diviner. The rite was sometimes witnessed by only the accusers and kin of the accused, other times it was enacted before many spectators. Three major ordeals were used. One combined oath-taking with imbibing a special drink or sometimes food. In an Akan polity along the Gold Coast, the accused took a drink before the diviner’s sacred rod, was smeared with supernaturally powerful ingredients, and then called on the god for death in various horrible ways if he or she was guilty. In the Kongo region, the nganga (the priest–diviner) prepared the drink of “purification” or “purging” from the red bark of an ordinarily poisonous tree; he then intoned before the gods and those present that an in nocent person would drink it and remain well.19 A second ordeal used heat to test the flesh of the accused. In Kongo, the diviner put a rock in a pot of boiling water, which the suspect had to remove; along the Sierra Leone River, the diviner might add a special bark to the boiling water to make it stronger; in a region of the Gold Coast, a cowrie shell had to be retrieved from a pot of boiling oil. If the person was guilty, the arm would become ulcerated.20 Yet a third ordeal put to test the suspect’s tongue. In the kingdom of Benin, the diviner passed a cock’s quill through the tongue of the accused; among the Akan on the Gold Coast, the diviner might use a sewing needle. Easy removal demonstrated innocence.21

In all these tests, we can see what leeway the diviner had in the choice of drink and ointment and their strength, the temperature of the water, and the size of the cock quill or needle and in the examination of the flesh or tongue afterward. Father Cavazzi reported that the nganga had met with both accused and accusers before the test ceremony and had negotiated gifts from each side. In the Sierra Leone region, the surgeon Atkins heard that the diviner made the “red water” used in the oath-test drink stronger or weaker depending upon what he had surmised about the guilt of the accused. Rømer, too, said that among the Akan, small gifts to the diviner affected the outcome for the suspect in cases such as theft, but in most instances the diviner must have been influenced by what he or she had learned about situation and the crime.22

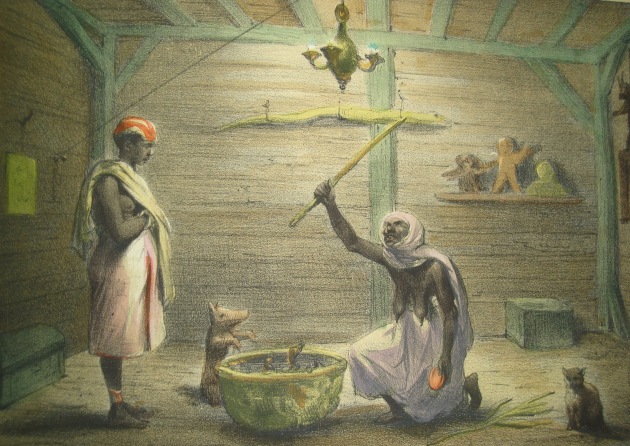

Figure 2. The hot water ordeal in Central Africa. Watercolor by Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, “Missione evangelica al regno de Congo, 1665–1668”; courtesy Manoscritti Araldi, Collection of Michele Araldi, Modena, Italy. Reproduced in James H. Sweet, Recreating Africa. Culture, Kinship and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Hill and London, University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 124.

Figure 2. The hot water ordeal in Central Africa. Watercolor by Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, “Missione evangelica al regno de Congo, 1665–1668”; courtesy Manoscritti Araldi, Collection of Michele Araldi, Modena, Italy. Reproduced in James H. Sweet, Recreating Africa. Culture, Kinship and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Hill and London, University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 124.

A nice example of this is the choice of the river test along the Slave Coast in the kingdom of Hueda: the guilty person would sink, the innocent would swim. “They all swim well,” commented the Dutch observer Bosman, “I’ve never seen anyone convicted.”23 Clearly, the diviner knew when to allow this ordeal.

If found guilty, the person was given a sentence by the king and his council of great men, by a regional governor, or by a local headman and his advisors.24 The death penalty was possible in cases of murder and other crimes viewed as especially vicious, such as witchcraft, but it was by no means regularly pronounced. For adultery, death was the expected punishment for one of the many wives of a king or of a great governor and for her lover. A French ship-captain witnessed such an execution in the kingdom of Hueda in the 1720s: the man was burned to death, the woman was scalded with boiling water by other royal wives. But if adultery were committed by one of the wives of a rich merchant, a large payment to her husband could excuse her, whereas the wife of a simple farmer might be beaten and sent away and her lover’s property confiscated by the husband. Indeed, fines and compensatory payments were often the preferred penalty—very much higher if the victim had been a free person rather than a slave—and execution performed only in the absence of payment. Theft was almost always punished with payments: the restitution of the stolen goods and fines, adjusted to the ability of the person to pay. Thieves who could not pay were beaten. Kidnapping was sometimes repaid by the recompense of a male or female slave.25

And yet for all these crimes, one punishment was becoming more frequent: enslavement. In the past, exile had been a possible penalty for serious crime, which usually led to enslavement in Africa itself. But now the punishment involved the sale of the criminal to European slavers. In the somewhat exaggerated words of Francis Moore, a factor for the Royal African Company in Senegambia in the early 1730s. “Since this Slave-Trade has been us’d, all Punishments are chang’d into Slavery; there being an Advantage in such Condemnations, they strain very hard in order to get the Benefit of selling the Criminal. Not only Murder, Theft and Adultery are punish’d by selling the Criminal for a Slave, but every trifling Crime. . .”26

In the outer reaches of the kingdom of Benin decades later, Equiano’s Igbo villagers were selling to African traders not only their war captives, but also “such among us as had been convicted of kidnapping or adultery and some other crimes, which we esteemed heinous.”27 Although the large majority of slaves transported across the Atlantic continued to be captives of war or victims of kidnapping, persons condemned for a crime were among them, especially when they could not pay fines or make compensation.28

There were two memories the Africans would not have carried across the ocean. Few of them would have seen or heard of incarceration as punishment for crime among their own peoples. In their forts along the Guinea Coast, the Portuguese, Dutch, and other European traders might include a small improvised prison, but this was for offenders among their ranks or, on occasion, for a trouble-making African in their own circle, and was quite apart from the spaces reserved for captive slaves. The great rulers of the Songhay Empire were said to have used some form of confinement for political offenders in the late fifteenth and sixteenth century on an island near their palace at Gao. But, on the whole among the African polities, structures of incarceration for criminals were not built until the nineteenth century. Persons accused of crimes were kept from running away by their families in their compounds. Enclosurewas conceived rather as a setting for ritual exclusion, as when menstruating women had to live in a special hut.29

Furthermore, although the execution of persons condemned to death in kingdoms along the Guinea Coast and inland involved painful and prolonged torture and humiliation of the body (not to mention the degrading treatment of the corpses of war captives), branding and mutilation were rarely used as penalties for living persons. One of the few examples was emasculation, said to have been practiced on the royal eunuchs of the kingdom of Oyo because they had previously been engaged in incest, bestiality, or adultery with one of the king’s wives. Scarification of the face and body and piercing of the hair and lips were not “mutilation,” but rather ancient and honorable marks of identity, beauty, and status.30

The Africans purchased by European traders were kept in barracoons while awaiting the boats that would take them to the Americas; at Elmina Castle, the prisons were damp ground-floor rooms similar to those used for storing goods. “We pay two pence a day,” said a factor for the Dutch West India Company, “which serves to subsist them like our Criminals on Bread and Water.”31

The slave ship itself was a “portable prison,” in the phrase of one of its eighteenth-century defenders, a “floating dungeon” in the words of a critic, to which the slaves arrived in chains or ropes and branded with the name of the Company or the purchaser that owned them.32 The ship operated under instructions from the Company or other owner, who warned that precautions were required lest the crew be attacked by their African cargo, but who also insisted that the slave men and women “not be defiled or mistreated by any of the officers and crew members” (to quote from those given to a Zeeland ship, De Nieuwe Hoop).33 How these instructions were fulfilled depended upon the captain, his surgeons, and his sailors, the latter themselves often ill-paid and harshly disciplined. William Snelgrave, captain of many an English slave voyage, instructed his crews that “Negroes be kindly used,” as this was the best way to avoid revolts. Once the boat was well away from the coast, he allowed irons to be removed from the men, a practice reserved on many boats only for women and children. But any “disturbance” the “kindly” captain met with “severe” flogging and other punishment, and any attempt at mutiny was met with death.34

For the Africans, as is well known, the discipline and punishment of the “portable prison” were devastating, leading to death and suicide—in addition to the pain and humiliation of rape and the mortality caused by ill health and disease. But in the holds, other activities were taking place that created bonds and perhaps even a form of “justice” among the Africans. Although captains had sometimes acquired their human cargo from different ports or had arranged to have different language groups represented among their hundreds of slaves so as to minimize the danger of revolt, nonetheless there were always groups who shared a language (some were from the same family or village) or could understand related languages. A provisional pidgin was surely created, and some Africans from coastal regions knew the Portuguese pidgin that was current along the Guinea Coast. A sort of kinship was established among those chained or sleeping or working on the decks near each other: in Suriname survivors of the voyage recalled the tie afterward by the Sranan term sippi, shipmate.35

Leaders emerged among the captives, both on their own and created from the officers’ deck. The captains themselves appointed “quartermasters” or “bombas,” as they were called on the Danish ships: slaves who, they believed, would be cooperative and who, in return for extra provisions, would help organize the eating arrangements and oversee the crews washing the decks. Some of these leading men and women may have also been diviners or healers in their African communities. Ludewig Rømer actually recommended to Danish captains that women healers take over from the ship’s surgeons in the face of African illnesses such as worms, and that they be given oils and spices with which to prepare their remedies, while an English captain reported on the presence of “religious Priests” on his ships in the 1760s to 1780s and their role in urging insurrection. But all these leaders could have drawn on techniques that they knew, or improvised new ones to arbitrate and quiet the quarrels that broke out among men closely shackled or from tribes with grievances against each other.36

And one of the wives of the great King Agaja of Dahomey, sent off to slavery for having aggrieved him, found her place on the women’s deck of Captain Snelgrave’s galley Katherine in 1727. The Captain saw her as an agent of pacification of the “noise and clamor” of “the female captives who usually give us great trouble,” but I think we can perceive her as providing leadership and arbitration that was of service to the women as well.37 In such ways did the Middle Passage help survivors get started toward establishing their own justice one day on shore. ♦

Once docked in Paramaribo, cleaned and oiled for the auction block, purchased and branded again by a new owner, the African was rowed up one of the rivers to the plantation at which he or she would henceforth work and live. The plantation will be the site for my next discussion of “criminal justice” even though the people deciding on offenses and punishing offenders were authorized by property ownership (“domestic jurisdiction,” in the Roman law) rather than as agents of a “state.” Indeed, the courts of Suriname themselves had the mixed status of so many colonial governing institutions of the day: they were the creation of a chartered Society in the Netherlands, which owned the colony through purchase, while acting under the aegis of the States-General. (Already we can see that Suriname is a fitting illustration of Lauren Benton’s “legal pluralism.”)

In contrast with Louis XIV and his Code Noir, the States-General issued no edict governing the features of slave conduct, treatment, and religion in Dutch colonies. Rather the Suriname governor and the Court of Policy and Criminal Justice issued ordinances from time to time, spelling out the permissible limits for the punishment of slaves on the plantation. In their general form, they resemble the rulings on the master’s punitive power over slaves found in other Caribbean societies.38 Early in the colony’s existence, in the 1680s, the governor had prohibited owners from imposing death or mutilation on their slaves. The next major edict on the matter was more than seventy years later in 1759. No manager or white officer was to use rods on a slave, but only the customary local whips, with which they could give between twenty-five and fifty or at most eighty moderate strokes and only on the lower limbs. They were to order their black drivers to behave accordingly. Any heavier punishment could be given only at the order of the owner, who would place limits according to his or her own scruples. No slave should be threatened with being shot except in case of absolute self-defense. The penalty for violation was 300 Dutch guilders. A 1784 ordinance repeated these limitations and the penalty for violation, although it now forbade whipping a slave who had been hanged from his or her wrists from a tree.39

Fines were in fact imposed only when the killing of a slave was discovered and prosecuted (as we will see more fully), although excessive cruelty on a plantation could tarnish the reputation of an owner or manager. Still, when the governor proposed in 1762 that something more than a fine be instituted for beating a slave to death, the councilors on the Court of Policy and Criminal Justice, all of them plantation owners, demurred: “Athough no owner should ever arrogate the power over life and death over his slaves, it is nonetheless of the utmost importance that slaves should continue to believe that their masters possess that power. There would be no keeping them under control if they were aware that their masters could receive corporal punishment or be executed for beating a slave to death.”40 The law remained as it was.

Punitive practice varied on the plantations. Suriname was known throughout the Caribbean for the extravagant cruelty of plantation punishment. Observers’ accounts from Suriname in the late seventeenth through the eighteenth century talk of extended beatings with whips chosen for their sting, after which the open wounds were rubbed with lime juice and pepper, and of the “Spaansche Bok,” (the Spanish buck, as it was called), when the slave was whipped first on one side then the other, with hands tied around the knees and a stick holding him or her to the ground. The latter was declared illegal in Suriname only in 1828.41

Especially telling is a play written in 1760 or thereabouts, in Sranan and Dutch, by Pieter van Dyk, long-time manager of a coffee plantation on the Commewijne River. The play, The Life and Business of a Suriname Plantation Manager, was included in a book of instruction on the Creole language of Suriname, as part of Van Dyk’s effort to convince “owners and managers . . . to make [themselves] respected and loved, without committing the inhuman cruelties that sometimes become part of the work.” Van Dyk used the topos of the drunken plantation manager acting in the absence of the owner: the manager orders his black driver to beat a woman slave till her skin comes off her back for being late bringing his coffee and to give the Spanish buck to a male slave asking to get off work because of being sick and to another for picking unripe coffee beans. The manager ends up shooting and killing his hunter slave because he had failed to bring back game two days running and then had protested against being punished. Van Dyk’s cruel manager, a composite of actual cases, illustrates the conduct targeted by the ordinance of 1759.42

John Gabriel Stedman’s descriptions of what he saw during his Suriname years (1773–1777) included punishments ordered by owners and managers both. His book, written after his return to Europe and published only in 1796, was in part a defense of slavery as beneficent for Africans, as long as it was humanely conducted, and in part a ferocious attack on the cruel punishment of slaves. (Indeed, his vivid pictures of that punishment, some of them engraved for his Narrative by William Blake, were intended to arouse indignation against the perpetrators and empathy for the slaves.)43 It was not the simple fact of beating that bothered him: in the Netherlands, where he had grown up, he was accustomed to seeing servants and workers beaten by masters and mistresses, and he was glad that the “unmerciful whipping” of his own father had cured him of a boyish habit of petty stealing.44 While in Suriname, he beat his slaves, for example, for slipping their boat away from his boat on the Commewijne River, and he beat the soldiers under his command for theft.45

What he deplored for the plantation slaves was the excess in punishments and their inappropriate use. (Likewise he had earlier opposed the “despotick cruelty” of officers in his military unit back in the Netherlands, who executed or whipped soldiers through the streets for small infractions.46) One of his first sights in Suriname was a woman who had been given 200 lashes and forced to bear a heavy chain attached to her leg for months as punishment for having simply failed to meet her work quota. Visiting plantation Sporksgift, Stedman learned that his friend, the Scottish owner John MacNeil, had ordered the hamstringing of a handsome young slave because he had been running away from his work. On L’Espérance plantation, where Stedman’s military post was established, the manager departed after flogging a slave to death for having let another slave slip out of his hands to the woods. “His humane successor,” Stedman commented sarcastically, “began his reign by one morning flogging all the slaves of the estate, male and female, old and young . . . for having [over] slept their time about fifteen minutes.” Stedman then visited a neighboring plantation on the Commewijne only to come upon a young unclothed woman tied by her wrists to the branch of a tree, her back bleeding from 200 lashes given by the black drivers at the command of the manager– the punishment prohibited a decade later in the ordinance of 1784. “Her only Crime,” Stedman discovered, “had consisted in her firmly refusing to submit to the loathsome embraces of her despisable executioner, which his jealousy . . . construed to disobedience.”47

Of course, there were plantations where such practices were not found. Stedman singled out Mrs. Godefroy, the elderly widow with whom he often dined, as a model of the good proprietor. Born of English parents in Suriname in 1713, Elizabeth Danforth had outlived two husbands, who had left her sugar and coffee plantations with hundreds of slaves. Victor-Pierre Malouet, a French adminstrator of the nearby colony of Cayenne, visited her sugar plantation in 1777 and confirmed Stedman’s judgment: “the most serious punishment [for the slaves] is being prohibited from seeing their mistress and from being on her path when she passes by. Any one of them would prefer a hundred strokes of the whip to this excommunication.” Although it seems unlikely that Mrs. Godefroy’s slaves would describe their feelings in Malouet’s words, it may well be that Mrs. Godefroy had instituted on her plantations a policy of very limited use of whipping.48

Figure 3. The whipping of a slave with her

wrists tied to a tree in 1774. Source: Stedman,

Narrative, vol. 1, facing p. 326, engraved by

William Blake after a drawing by Stedman.

Mrs. Godefroy’s plantations were not shaken by slave up risings over the decades, and according to Malouet, her slaves actually kept Maroon incursions at bay. Such stability is one of the possible signs of a plantation conducted in a fashion at least tolerable to its workers. An example is Fauquemberg sugar plantation on the Commewijne during the almost twenty years (1750–1768) it was managed by a recently arrived Dutchman named Anthony Tielenius Kruythoff. The plantation had been founded in the early eighteenth century by a Dutch settler family, but by 1753 its owners were living in Amsterdam and Kruythoff was administering and running the estate himself. During his tenure, the slaves, roughly 190 in number, did not organize uprisings or escapes to the Maroons, nor did the Maroons attack the plantation. The birth rate was relatively high among the slave families, and a good number of the children lived to be young adults.49

Kruythoff was an officer in the Suriname militia and, with a troop of armed men, was called upon to quell slave uprisings along the Commewijne and to track escaped slaves in the rain forests. In the midst of slave rebellions in 1759, he blamed such resistance on masters and managers who overworked and underfed their slaves, threatening to shoot or behead them if they did not complete impossible tasks. He himself kept a close eye on the white driver at Fauquemberg and rewarded his slaves on occasion with gifts.50 I suggest that the tolerability of the regime at Fauquemberg and other such plantations goes beyond Kruythoff’s formulation: it emerged not just from the humane heart or practical concern for property of masters and managers, but from the systems of governance and justice organized among the slaves themselves. We have glimpses of such systems in reports from Jamaica and Antigua; here I would like to sketch out a fuller picture of the possible structures and practices of slave-initiated justice in Suriname.51

The African newcomers to a Suriname plantation took weeks and months to find their way among the slaves. Given a new name for use at least among the whites, assigned a place to live in the palm-leaf-covered ningre hosso (slave houses) and a work slot in the fields, buildings, waters, or houses of the plantation, the African gradually learned the local Creole tongue—Neger Engelsche or Sranan on the Christian plantations, Dju-tongo (or Saramaccan as it came to be called) on the Jewish ones. The discipline and punishment practices found on the Suriname plantations would have contrasted in some ways with what Africans would have observed in the multiple slave systems back home. On the one hand, the African owner could dispose of the life of his slaves without responsibility, at least in non-Islamic lands: for example, the great kings of Dahomey in the eighteenth century were being buried with hundreds of their slaves, while in the nearby kingdom of Benin, a person sentenced to death for a murder might offer a slave in his stead.52 On the other hand, even in those African societies in which slavery did not slide into a kin relation and which were “hierarchical [and] market oriented,” the exploitation of slave labor was not accompanied by so punitive a regime. I follow Martin Klein here, who found the harshest treatment of African slaves was at the moment of their capture and the early weeks of their “seasoning,” where they might be forced to sleep in chains. “[Even] in the most market oriented African systems,” says Klein, “slaves worked for their masters about half as much as in the U.S. South.”53

In Suriname, the figures of authority and prestige within the slave community prepared newcomers for the shock of the local regime.54 Such men and women were central to the institutions and procedures on the plantation—some carried over from Africa, others improvised or invented in Suriname—which helped slaves survive and sustain an independent cultural life, keeping peace among them and acting as buffers against or setting limits to the arbitrary power of the owner and the owner’s agents. These slave leaders gained their authority partly through their own doing, partly through the decision of the owner or manager.

Let us begin with the black driver, called negerofficier or zwarte officier (“black officer”) in Dutch and ningre bassia, or just bassia in Sranan. (Interestingly enough, the word bomba was sometimes used in Suriname for the black driver, thus carrying over a title familiar from the slave ship.)55 Up to now in my account, we have seen the black driver in Suriname with a whip in his hand, punishing the slaves at the command of his white superiors. But he was a complex figure, who had the ear of his superiors and, if he were to have any success at all, was trusted by his fellow slaves. A plantation with many slaves—say, 125 and higher— usually had two or even three bassias, whereas those with fewer slaves had only one. Appointed first as young men, the bassias either were creoles, that is, born in Suriname, or had arrived at the plantation at an early age, and they were virtually always the sons of black parents rather than of a black slave woman and a white man. Sometimes they were field workers or hunters, other times plantation craftsmen. At Fauquemberg, the field worker Cupido and the young creole Quimana appear as bassias in an inventory of 1753; a few years later, Quamina is the senior bassia together with the young fieldworker Bienpayé, the two of them holding those posts through 1768.56

A bassia had to combine the political skills of an African chief, learned from his father and/or the many other newcomers from Africa on the plantation, with creole savvy about what was necessary to tell their white bosses, to whom they spoke in Neger Engelsche or Dju-tongo. For a bassia to be acceptable to the slaves, it was said, he must never raise his whip to punish on his own behalf or ever be believed to be doing so. In Van Dyk’s play, the black driver beats only at the manager’s command, while begging his drunken superior to hold back from such harm: “Have mercy, master. I gave that woman a hundred lashes already.” He tries to help a slave wife free herself from the manager’s sexual demands, although he is unsuccessful in his efforts.57

The historical record presents bassias more forceful than Van Dyk’s respectful slave. As one white driver put it to his fellow officers, “Never trust a bassia, for his solidarity lies not with the plantation staff, but with the slaves.” A final weapon in the bassia’s hands was contact with the Maroons. In some instances, he was a major figure in resistance to the Maroons: this occurred when the slaves did not want any of their number, especially their women, to be kidnapped. In other instances, Maroon attacks on Suriname plantations were at the invitation of the bassias; and some of the mass escapes to the Maroons had bassias at their head.58 The bassia’s status is suggested in a painting made in 1707 or thereabouts by Dirk Valkenburg, an Amsterdam artist who was then bookkeeper and scribe for the sugar plantation Palmeniribo on the Suriname River. A religious dance is being performed in front of the slave houses, where some of the participants are possessed by the gods. The bassia stands tall and aloof, a European hat on his head and a small knife tucked into the strip of cloth around his hips.59 Of course, some bassias were seriously at odds with their co-slaves, and on occasion slaves accused the bassia of trying to poison one or more of their number.60

Putting pressure on the bassias from among the ranks of the slaves was an impressive group of skilled men and women, some born in Suriname, others youthful arrivals from Africa. The men were carpenters, coopers, bricklayers, and other plantation craftsmen, whose names appear directly below the black officers’ on the inventories. Such were the men the master or manager armed with rifles to accompany him and his white servants in search of runaways; this had the side-result of allowing the elite slaves to learn the location of Maroon trails. The women were cooks, knitters, and seamstresses, many of them also serving at the great house, their names appearing at the top of the lists of female slaves. (Amiba, the lead woman on one of the Jewish plantations, is actually called “officieresse”).

Figure 4. The bassia (black driver) surveys a slave dance at Palmeniribo plantation

Dirk Valkenburg, Slave Play in Suriname (ca. 1706–1707); National Gallery of

Denmark, Copenhagen, KMS376. © SMK Photo.

Some of these women had memories of African families where their mothers were co-wives; although there were surely quarrels among them, they helped sustain order and amity among the slave women, the field maids, and others. Sometimes, too, they had their own channels to the white bosses by which to seek favors or protection for their families and for other slave women.61

The third group of influential figures in the slave community were the religious specialists and healers, most born in Africa in the early generations, some born in Suriname. Every plantation had its healer or healers, whose knowledge of local plant lore, coupled with incantation, was more useful than the surgical implements kept in the plantation medical cabinet. Many plantations had a priest–diviner, known as a Lukuman in Sranan, or a priestess–diviner. Given the honorific name of Granman and Gran Mama, they called upon the gods and served humans in the ways we have seen in Africa.62

A few such sacred leaders were reputed throughout the colony. Granman Quassy was born in West Africa in the 1690s and spent his young manhood on a sugar plantation in Suriname. By the 1740s he was celebrated as healer, diviner, seer, and creator of obia, packets or amulets in which the various feathers, hair, shells, and other objects carried with them the presence and power of African gods., He was also the discoverer of a special bark that would bring down fever; transmitted to Linnaeus by a Swedish settler in Suriname, it was named Lignum Quassiae. Quassy toured to different plantations, whereas the priestess–diviner Gran Mama Dafina was consulted by her supplicants in her “secret chamber,” with its clay figures of persons and animals, its huge pot of water, and its live snakes—equipment similar to that found among the diviners of the Gbe-speaking peoples of the Slave Coast kingdoms.63

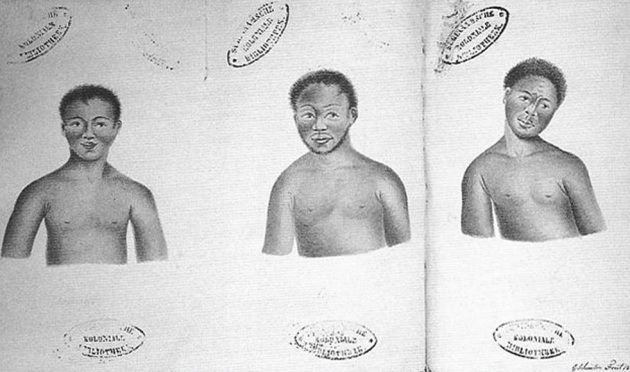

Figure 5. A woman diviner at work in Suriname, ca. 1830. Source: Pierre Jacques Benoit, Voyage a Surinam, 1839. fig. 36. Collectie Buku – Bibliotheca Surinamica

What kind of procedures of justice did slave leaders try to put in place on their plantations? Resistance to the master’s punitive regime could range from controlling the flow of information about slaves to the whites, on up to the threat or actuality of revolt. Discussion meetings were held to make plans. In Van Dyk’s play, the bassia meets together with a leading female house slave and several men; they call each other “master slaves,” “mastra negeri,” using the forms of customary politeness. They delegate one of the men to sneak away and inform the owner in Paramaribo about the brutality of the manager.64

We can eavesdrop on an actual meeting in 1707 at the sugar plantation of Palmeniribo with its 148 slaves, whose bassia we have just seen in Valkenburg’s painting. Mingo, a slave born in Kongo, had been preparing to visit his wife on another plantation, although the owner had forbidden him to do so. Whereupon the owner smashed Mingo’s canoe. Mingo then met with his brother Waly and several other blacks, who urged him to go the owner and demand compensation: “Mingo, you’re no man” [if you don’t do it], Waly said to him in Sranan, “Mingo jou no man.” “I am a man,” said Mingo. “You go then.” As it turned out Mingo’s mission coincided with other grievances on Palmeniribo, especially the owner’s revoking the previous owner’s grant of Saturdays free from work. Mingo led a delegation shouting “jou no meester voor mi.” An uprising ensued; some slaves escaped to the Maroons, others were prosecuted, but the slaves of Palmeniribo got their free Saturdays back.65

More significant was the justice established by the plantation slaves to arbitrate and provide punishment or compensation for offenses among themselves—offenses which, if they got to the ears of the manager or owner, would be punished by these whites; and offenses, such as poisoning and theft, which when they were brought to the notice of the Court of Policy and Crime, were prosecuted there, as will be described. As I put together what evidence we have, on those plantations that had a slave community with some coherence and effective leadership, the community preferred to deal first with its own offenders before deciding whether or not to yield them up to the owners or to the colonial court.

What were these offenses? Bad-mouthing another slave was surely one of them. The courteous language of address noted in the African kingdoms was carried over into the mixed Creole of Sranan and Saramacca. Whereas a black making a request to a white would say “Many thanks, Master, would you please give me that?” to another slave, he or she would say, “Thank you, thank you my dear beloved, I kiss your feet, do me that favor!” (“ Tangitangi, mi hatti-lobbi, mi boosi ju futu, du mi da plessiri”). The choice insult among slave men in Suriname was “you mama pima” (“your mother’s cunt”) and it aroused great anger.66 Early on, this kind of troublemaking had a Creole vocabulary to describe it, drawn both from an English and an African lexicography: lei, a takki lei, leiman (“lie,” “he’s talking lies,” “a liar”); kossi (“to scold,” “to curse”); gongossa, gongossaman (“slander,” “a slanderer”); kongro, kongroman (“malice,” “falsehood,” “a malicious person”).67

Another offense was theft, especially hateful among people who had so little that they could call their own and who put a high value on sharing. “The poorest Negro [in Suriname],” wrote Stedman, “having but an egg scorns to eat it alone, but were twelve others present and everyone a stranger, he would cut or break it in as many shares.” A stingy person was a “mombi”; a thief, a “furfurman,” was much worse. To protect one’s vegetable garden or one’s house from an intruder, Suriname slaves placed a kandu in front of it, an object made of rocks or sugar cane or some other material endowed with the threatening powers of a certain god: “All the fruits in my garden are being stolen; I’m going to put up a kandu” (“dem furfur tule janjam na mi plantasi, mi tann go putta kandu”).68 But the kandu’s power could not extend to everything, and thefts had to be dealt with.

Unacceptable sexual relations were yet another set of offenses. In regard to the sexual assaults and initiatives of the white male proprietor, manager, or driver, there was a limit to how much protection slave justice could provide, and slave men and women may not have always agreed on who should be protected first. In some actual cases and in Van Dyk’s play, the white man’s forcing sex on a married woman was viewed as the more serious violence, harming the wife and humiliating her husband. So Stedman told the story of a slave who harbored hopes for revenge for more than twenty years against a manager who had raped his mother and flogged his father when he came to her aid.69 Nonetheless, some slave mothers may have felt that protecting their unwed daughters was at least as important, unless they saw the sexual intimacy leading to favour for the family.

As for intimate relations among the slaves themselves, the African assessment may have persisted, that is, adultery strongly condemned, but “fornication”—to use the term of their European masters—tolerated as long as it occurred with persons approved by parents. Stedman (whose informants included his slave concubine and her mother) described the “passion of love” among slave husbands in Suriname as expressed in “the jealousy [they feel toward] their wives, to whom their resentment for incontinence is absolutely implacable.” But the sexual experience of the women before marriage, claimed Stedman, “gives the [slave husbands] no uneasiness.”70

The marital economy on the Suriname plantations differed from that remembered or recounted from African societies, where polygyny had been widespread and even a small farmer might take a second wife. On the plantations, male and female slaves existed in roughly the same number, with men often more numerous than women through the eighteenth century. In addition, the difference in power and prestige between the elite male slaves and the field hands was not so great as to make it easy for the former to possess more than one wife at a time. Polygyny was practiced among a minority of the Saramacca Maroons—the word “co-wife,” gambossa, is used among them by the late eighteenth century—and there were undoubtedly some examples on the plantations. But on the whole Stedman’s picture of the “happy” Suriname slave—marrying, divorcing, and remarrying by their own rules and rites—is the more characteristic one: “he never lives with a wife he does not love, exchanging her for another the moment he or she is tired.” Stedman went on to say that such serial marriage was less common among the Suriname slaves than it was in “a European state of matrimony.” In these circumstances, adultery could cause real trouble in the clustered households of the slaves’ quarters.71

Finally, there was physical harm, especially through poisoning, used to make someone ill or even to kill him or her. The desire to poison was fuelled by various grievances: revenge against someone who had stolen the affection of a lover or a husband or wife; envy of another’s status in the slave community; hostility against new arrivals, in the latter instance sometimes carried over from African political loyalties and conflicts. In 1757 a revolt began on a plantation called “La Paix” at the headwaters of the Commewijne because the owner wanted to transfer the slaves to another of his plantations downstream: the slaves feared they would be killed by poison and sorcery, as they claimed had happened to the last group of transferees. Indeed, poisoning was viewed with horror, for it was thought to be coupled with witchcraft: as healers drew on the gods to add force to their remedies, so poisoners drew on dangerous forces.

Some plantations had a wissiman, a sinister specialist in the harmful use of poisonous plants, the incantations that must accompany them, and the antidotes to the poison when called upon. A wissiman was always in danger of being denounced along with the person who sought his or her powers.72

When these offenses occurred or accusations were made about them, the slaves’ justice could go into action. Here we must piece together a scenario from what evidence we have from Suriname. A diviner—a lukuman—would start off to help find the guilty party, if no accusation had been made. As in African polities, the corpse being borne in its coffin was asked by the diviner for information about the source of his or her death: had he or she offended the gods? Had he or she been poisoned? If there were a murder behind the death, the coffin-bearers would be precipitated toward the evildoer. The Moravian Brother describing this practice in Suriname remarked that the “Obia man,” that is, priest–diviner, would have “already gained exact knowledge of who is guilty through his own research” and would have informed the coffin-carriers in advance.73 Granman Quassy, when called to a plantation to find a thief, divined with his gaze and with bird feathers. After inquiring about relations among the slaves, Quassy had each person walk by him while he turned the bundle of feathers in a glass; then he looked at each slave steadily in the face. “His pursuit suddenly made the heart visible,” according to one report.74

Once the accusation had been made and aired among the slaves, two ordeals to establish guilt or innocence are reported from Suriname, both variations on those used in the Guinea Coast kingdoms. In the kangra, the diviner smeared the person’s tongue with a paste from special herbs or leaves, then passed a chicken feather through it. If the feather went through easily he or she was innocent, if it did not, he or she was guilty.75 The oath-drink test was described among the Saramacca Maroons in cases of a person accused of murder or poisoning, and in all likelihood a version of it was used for some offenses on the plantations.76 Plunging the accused’s arm into hot or boiling water to retrieve a rock or some other object, which was found as an ordeal from the Gold Coast to Angola, was used to sort the guilty from the innocent among slaves in neighboring Brazil. Gran Mama Dafina of Suriname had a large pot of water in her sanctuary, and may well have used it for ordeals along with other kinds of divination.77 And then there was the river test used to establish innocence in the Slave Coast and Kongo: it was easy to arrange in Suriname and many of the slaves were good swimmers. In all these instances, a lukuman or diviner– priest on the plantation could seek information and listen to the gossip in the slave houses and adjust the scenario of the ordeal and the choice of ordeal accordingly.

Judgments in the wake of the ordeals would then be made, so I suggest,by the bassia in consultation with other important male and female slaves. It would resemble the slave tribunals described by a planter in Jamaica. “On many of the estates the headmen erect themselves into a sort of bench of Justice, which sits and decides privately, and without the knowledge of the whites, on all disputes and complaints of their fellow slaves.”78

Such a tribunal would not model itself on the Suriname Court Policy and Criminal Justice. Rather it would be a reworking of the council of the Guinea Coast kings with their great men or the meetings of village headmen and elders, but on the plantation with the addition of leading women—the cook, the senior house servants, the midwife—to the deliberations, not routinely found in African polities.79 In cases of insult and slander, theft, and adultery, the penalty would not ordinarily have been beating, the routine punishment of the master for such cases among slaves (“flogged Maria for cuckolding Solon . . . and stirring up Quarrels,” a Jamaica planter recorded in his diary in 1773). Rather the penalty would be compensation to the aggrieved, the African practice adjusted for Suriname; say, produce from one’s garden or a special garment or a bracelet or tobacco presented in a ceremony of abasement and accompanied by some sacrifice to the gods, or work services performed for the aggrieved party. The bassia’s whip must have sometimes been used as a threat to enforce the penalty, and actual beatings surely occurred in more serious cases. But it would have been difficult to carry out a major scourging unauthorized by the manager or master and keep it secret from them.

Poisoning and the associated sorcery were much more serious, feared all the more as one did not know whom the wissiman would strike next. In Africa, poisoning/witchcraft was punished by a cruel death or by being sold into slavery. In the rainforests of Suriname, the Saramacca Maroons, freely organizing their own justice, mutilated the sorcerer/poisoner’s body and then burned it. In Paramaribo the Court of Policy and Criminal Justice punished poisoning by death. On the plantations, then, the slave justice yielded the uncontrollable poisoner up to the authorities.80

The Court of Policy and Criminal Justice was composed of thirteen Protestant men, with the governor at its head; serving as its public prosecutor was an officer known as the Fiscaal, who was supposed to be educated in the law. The councilors, chosen for life by the governor from a slate elected by the settlers, were all prominent plantation owners, and only a small number of them had had any formal training in the law. Whereas Jan Jacob Mauricius, governor from 1742 to 1751, had studied both law and letters at Leiden, some of his predecessors and successors in that post and most of the councilors had never listened to law lectures either at that august faculty or at the university at Utrecht.81

Similarly to the courts in the Netherlands, the Suriname Court dealt with both matters of public order and criminal cases, and, as in the Netherlands, the sixteenth-century ordinances of Emperors Charles V and Philip II were the overall guide for criminal procedure. The Dutch republic retained these ordinances until the reforms of 1795–1809, that is, long after it had freed itself from imperial rule. In the Netherlands these codes, together with subsequent edicts and local regulations, allowed for harsher treatment of the poor than of the propertied in criminal procedure and punishment— especially of the vagrant poor. In the colonies such as Suriname, these codes, supplemented by the Roman law on slavery and subsequent local ordinances, allowed for an even greater gap between the treatment of slave and free, black and white in the course of criminal trial and punishment. Simply being a slave aggravated whatever offense one had committed. In the words of a jurist in Suriname’s neighboring colony Demerara: “[slaves] are more severely punished for the same offense than free men; their very condition, according to the criminalists, [is] supposed to communicate an aggravating quality to the offense.”82

The Court issued ordinances restricting the behavior of slaves in situations beyond the plantation.

1741: in Paramaribo, slaves must stand out of the way of white people on the streets; they must not carry canes or cudgels when they walk. They must not gamble or play dice among themselves and certainly not with white people; penalty for the slave players: being whipped along the streets of Paramaribo; for the white players: a fine. 1769: no slave, whether black or mulatto, is to go about wearing shoes and stockings or an extra large hat; penalty for repeated violation: the Spanish buck. 1750 and frequently afterward: slaves are forbidden to sing and dance publicly in the streets of Paramaribo or at funerals: penalty, the Spanish buck.

Interestingly enough, Governor Jean Nepveu, who signed the 1777 reissue of this ordinance, wrote in another place, “In Paramaribo, (the baljaaren [dancing] of slaves) was frequently prohibited altogether, and those caught at it were liable to severe punishment. But experience has taught that this has no effect, and even if it were punishable with death, this would probably only increase their desire for it. . .”83

Such infractions as these did not generate full trials before the Court, but were evidently dealt with and punished by prosecutor and the governor’s officers. The slave cases most frequently brought before the Court of Policy and Criminal Justice for prosecution were those to which the death penalty or bodily mutilation, such as an amputated leg or hamstringing, was attached. Records of 146 trials in which slaves were sentenced between 1730 and 1750 have been retrieved from the Suriname archives and studied by a scholar descended from an old Suriname planter family. These trials do not cover all the criminal charges against slaves in those years. The executioner’s list adds additional names, and other slaves could not be brought to trial because, as the governor’s journal indicated with regret, they had escaped to the rain forest and had not been recaptured. Still this collection of trials suggests what kinds of cases found their way from the plantations for judgment by the court. The largest single category, 36%, involved poisoning; 7% involved the murder of white people by other means; 6% involved the murder of other slaves; and 7% involved plotting or conspiring to murder. Another 12% involved theft, burglary or receiving stolen goods, probably in all cases the property of white people, and 11% involved slaves who had run away and been caught. Some 8% involved some form of rough treatment, insulting of, or impudence toward whites. Yet another 5% concerned plantation mischief, such as falsely accusing someone of poisoning or assisting Maroons during a plantation raid. In 8% of the cases, the remaining records did not include the offense. Of the slaves’ sentences, 82% (114 people) were condemned to death, at least a dozen of them by hanging from the gallows with a hook in their ribs.84

The slaves’ trials were conducted by the “extraordinary” procedure, as it was called in the Netherlands and in other Roman law countries. In the words once again of our jurist from nearby Demerara: “Extraordinary process is a summary mode of proceeding to avoid the delay of an ordinary criminal suit or process, which latter is conducted in the manner of a civil suit. It can only take place on the investigation of crimes which involve corporal punishment.”85

This procedure was rapid and without counsel, and made it simpler to order torture to obtain the desired confession when the legal proofs allowed it during the trial, and torture before execution to extract the names of accomplices. In Suriname the accused slave was taken to the prison at Fort Zeelandia and interrogated through a Sranan or Saramaccan translator by the prosecutor and two members of the Court; other witnesses to or parties affected by the crime were questioned as well. Lacking detailed information on the trials, we do not know whether the Court actually followed the rules of Dutch–Roman law that required a certain amount of incriminating testimony or evidence before torturing a slave in hope of confession, “the queen of proofs” and a necessary prelude to a sentence of execution. In Amsterdam, the courts did so, and presumably the Suriname Court lived up to such rules for white people accused of a serious crime. Whatever the case, the accused slave was more likely to be stretched on the rack or otherwise tortured in Suriname than an accused working man or vagabond in eighteenth-century Amsterdam.86

Figure 6. Hanging of a slave by a hook in his

ribs in 1773. Source: Stedman, Narrative,

vol. 1, facing p. 110, engraved by William

Blake after a drawing by Stedman.

How might the slave have responded to torture? The body in pain was part of most African ordeals and all European torture. But in the African ordeal, after the accused had sworn in an oath not to have done a certain act, the body itself spoke of guilt and innocence through festering or healing or vomiting or good digestion and other signs, whereas in the European torture, the pain was to induce a full verbal confession. Indeed, Stedman’s heroic slave refused under torture to give the Court the information it wanted—the whereabouts of the Maroons and their actions—and instead, as we saw, recounted his own story of being treated with unjust cruelty and then fell silent. (We recall, too, that this slave had been born in Africa, and would have been trained to endure pain during his youthful initiation ceremony.)

We have a clue to the slaves’ reaction. In 1745 the Court observed that neither torture nor the prospect of a painful death aroused horror and fear among slaves who had been accused of poisoning of persons or animals, for they believed that once dead, they would soon return free to their own land. (The Court was here giving a version of the belief that one part of the soul, the jeje, as it was called in Sranan, situated in the heart, would return to the ancestors or to an ancestral god at death; for some slaves in Suriname and elsewhere in the Americas—especially the “salt-water blacks,” who had been transported across the ocean—this also took the form of the soul’s return to the land of the ancestors.87) To instill fear, the Court proposed a new punishment for such poisoners and others “guilty of a death sentence . . . for extremely abominable offenses”: to have their ears and tongues cut away and to be condemned to work the land for the rest of their lives in chains at Fort Amsterdam or elsewhere in isolation—not only men separated from women, but each cut off from all society with other slaves.88

This dreadful proposal, inspired by Governor Mauricius, was much more punitive than the houses of correction to which some criminals were condemned in Amsterdam at the time. It seems not to have been put into effect, or if it was, it was short lived; in any case the governor was soon caught up in what he called a “cabal” of planters and was replaced in office in 1751.89 We can nonetheless reflect on the Court’s claim that slaves did not fear painful torture or death. Apart from youthful training to endure pain or beliefs about the destiny of the jeje, slaves may not have respected the procedure by which a personal confession was to be extracted through torture. Certainly the many Africans among them at that date would have found it a strange and dubious procedure of which their gods might disapprove.

Interestingly enough, by 1778, the Saramacca Maroons, who conducted their trials in the rain forest independently of the colonial government, had introduced torture to get a confession from people accused of sorcery and poisoning. The priest–diviner made his inquiries and then conducted ordeals as on the plantations; once a person had been found guilty of poisoning by the tongue ordeal or oath drink, he or she was asked why and how the murder was committed. If no answer was given, the person was strung by the thumbs from the branch of a tree, with the feet weighted down by a stone, and beaten by the victim’s kinfolk until a detailed confession was forthcoming. Execution followed.90

This procedure was almost certainly an adaptation in Suriname by Maroon Creoles. Many painful ways were used to put the body to the test and to punish it in the Guinea Coast polities and in the kingdoms of Central Western Africa, as we have seen, but torture to extract a confession is not known to have been one of them. Perhaps Christian missionaries in Kongo or Angola recommended to some of their princely converts the introduction of torture to coerce confession, but if so, it has left no certain traces in the sources.91 In Suriname, the Saramacca Maroons made peace with the colonial government in 1762 and settled down to elaborate their institutions. By the 1770s, most if not all their leading figures were creoles, and in order to deal with the dangerous figure of the sorcerer/poisoner, they took over a European mode of prosecution, drawing their method of torture from a punishment used on the plantations. Possibly, too, the insistence upon confession was not only a practical matter for future peace keeping among the Saramacca Maroons, but was also encouraged by the presence in their midst of the Moravian Brethren. The Brothers won very few converts to Christianity, but those who did abandon their old gods, such as the tribal chief Alabi, embraced the habit of confessing their past false beliefs and “superstitions.” Perhaps this style jumped the border to the devotees of the Afro-Suriname gods.92

I think we see here a divergence between the slave communities on the plantation and the Maroon communities in the rain forest. In the confined space of the slaves’ quarters, torture would have introduced endless disruption among them and would have been impossible to conduct without coming to the ears of the white driver, the manager, and the owner. Might as well stick to the kangra.

But let us turn to a divergence of greater import for the slaves: that between the penalty for a slave who murdered another slave or a white person and a free person who murdered a slave. We have no direct commentary from the slave community, but Stedman expressed indignation. The manager of the plantation L’Espérance, who flogged his neighbor’s slave to death in a frenzy of fury, was greeted with a civil suit for property loss, rather than a criminal suit: he was fined 1200 florins, 500 to the Court and 700 to the neighbor. Stedman noted about this and the killing of other slaves by managers or owners: “It [is] a rule in the colony of Surinam that by paying a fine of 500 florins per head, you are at liberty to kill as many Negroes as you please, with an additional price of their value should they belong to any of your neighbors, and then the murder first requires to be properly proved, which is extremely difficult in this country, where no slave’s evidence is admitted.”93

We can follow this disparity in the story of two murders, their investigation, and outcome: one of a black woman slave by the manager of her plantation, the other of a white plantation owner killed by his black bassia.

In 1743, Benjamin Pousset was the manager of Sinabo, a sugar plantation on Commetuane Creek off the Commewijne River, owned by a Suriname heiress who lived with her Dutch husband in the Netherlands. Pousset had been born in Utrecht and had been a surgeon by trade before coming to Suriname and settling there as manager of Sinabo. Now aged forty-two, he had buried his wife on the plantation five years earlier. Ninety-five slaves were working under his irascible command in the early fall of 1743, but thirty to forty slaves had died not long before. Given scanty provisions by Pousset and inadequate land for their own gardens, many were weak with hunger. And, as the slaves were to tell the story—the carpenter Antyn, the sugar boiler Jafet, and others— Pousset brutally beat the slaves until they were ill, ignoring them as they sickened and died, and even drowned a slave in a nearby creek as punishment. When crossed by his bassia, the cooper Isaac, Pousset replaced him with the malleable Coffy.94

Meanwhile Pousset developed a particular animus—a “pik,” the slaves said—toward the slave woman Serie, accusing her of being a poisoner and responsible for the deaths. Given 200 lashes, Serie still denied the accusation. Pousset ordered a slave woman to hold her to the ground under an orange tree while he burned her ankle and hands until she confessed. Although Serie begged for the torment to stop and screamed that she would rather he kill her, she still denied any guilt.

Pousset had all the slaves summoned from the fields and denounced Serie as a poisoner. The men and women shouted loudly in her defense: she had given no poison to anyone, but had rather brought ten children into the world for the plantation, several of them still alive. Whereupon Pousset beheaded Serie. He ordered his officers to bury the body and dispose of the head, but Serie’s son Sondag, the former bassia Isaac, and two other slaves took the head to Paramaribo and made a complaint to the public prosecutor.

An inquiry was begun by one of the councilors of the criminal court, Hendrik Talbot, owner of a nearby sugar plantation.95 Talbot’s official report, based on his interviews and examination of the plantation record books, confirmed the denial of food at Soribo, and suggests that he believed the stories of the slaves. The three white men who worked at the plantation—the bookkeeper, a miller, and a carpenter—confirmed Pousset’s ill-treatment of the slaves, and said that he had even bragged about it to them. But they insisted that they had not been present on the plantation at the time of the torture and murder of Serie.

In his interrogation, Pousset denied all wrongdoing, and claimed that the slaves “had it in for” him: some years ago, two of them had even tried to throw him into the sugar kettle. Meanwhile the testimony of slaves against white people had no status in the law: it could not counter Pousset’s denial and could not constitute the kind of “proof” that by the Criminal Code would justify torturing Pousset for a confession. The Court decided not to torture the manager about what he had done to the slave Serie, but was uneasy enough to delay his release until “further deliberation.” As the gods would have it, Pousset died in prison before they could meet.

The Pousset affair moved the public prosecutor to comment to the Directors of the Society of Suriname, “One breaks a slave’s neck here more easily than one drowns a dog back in the fatherland.” He went on to urge reconsideration of the Court’s frequent practice of dismissing the complaints of slaves and sending them back to their masters. Moreover, abusive managers were costly: the twenty-eight slaves that Pousset had let die of hunger deprived the absentee owner of Sinabo of some 12,000 guilders.96 The prosecutor did not discuss the Court’s predicament in regard to Serie’s murder: that Pousset could not be condemned on the basis of testimony from slaves alone. This feature of the law he evidently accepted without question. But his reaction to abuse on the plantation was surely part of the anxiety that finally led to the Court’s ordinance of 1759, which, as we have seen, spelled out the precise limits on the kinds of punishments that could be administered on the plantation.

The second murder illustrates the disparity between slave and master in regard to punishment. Similarly to Van Dyk’s play, it shows the dramatic mixture of social and personal grievance in the lives of slaves. The events took place in February 1750 at Bethlehem, a large plantation on the Commewijne River with approximately 200 slaves tending its coffee bushes. Its owner, Amand Thoma, was of Huguenot ancestry and had long been resident in the colony. A captain in the burger militia and an elder in the French Reformed Church, he was an active figure in local politics, part of the “cabal” of French planters currently challenging the authority of Governor Mauricius. Attentive to his coffee plantation, Thoma was not known as a brutal punisher: he was no Benjamin Pousset, about whose horrors he would have heard from Hendrik Talbot, godfather to one of Thoma’s children. But Thoma did run Bethlehem with a stern hand, arousing the resistance of the slaves by oppressive work schedules and demanding their labor even on Sundays. In late 1749, the bassia Coridon and other Bethlehem leaders began to plot an uprising and an escape with slaves from two nearby plantations “to seek another land.”

But there was more to their complaint. Aged almost sixty and a widower since 1738, Thoma summoned slave women to his bed at night, shifting wives from one man to another to placate the aggrieved husbands. His most important liaison was with Eva, one of the few Amerindian slaves still found on Suriname plantations in her day (a “bokkin,” as Thoma called her, using the settlers’ colloquialism for the indigenous population) and who by February was clearly pregnant. Coridon’s coconspirators later told two different stories about Eva and Coridon. By one, which seems the most likely, Eva was Coridon’s wife. By the other, the master had been calling Coridon’s wife Bellona to his bed, and Coridon had become intimate with Eva out of revenge. In either case, the bassia was jealous of Thoma and wanted Eva’s child to be his own. “If a black child is born,” he said to his fellow slaves, “the master will seek revenge.” On the evening of February 21, 1750, Coridon entered Thoma’s room and killed him while he sat smoking; another slave, Gallien, killed the plantation scribe at his writing desk.97

The plantation was plundered, and all the slaves but the heavily pregnant Eva and a few old people fled Bethlehem to join escapees from the other two plantations. Pursued through the rain forest by many militiamen, a number of the men and women were found, including Gallien, and finally weeks later Coridon himself. Coridon was interrogated in Paramaribo on April 9, and seems to have offered a somewhat improbable testimony that was intended to protect Eva and show the master up as a scoundrel. “The bokkin Eva was not at all guilty and he had no part in her pregnancy.” Nor was he greatly jealous, he claimed, when his master brought his wife Bellona to his bed all the time. His jealousy had been aroused when the master had taken another wife, Bessolina, from him and given her to a black named Hector.98

The captured slaves were summarily questioned and executed, some hanged from the gallows by a chain in their ribs, others burned alive, others broken on the rack. As for Coridon, he was tortured and then his body was pulled apart by four horses on June 17, 1750.99 The executioner would have been a black slave: “the publick executioner . . . in this country [is] always a black,” said Stedman, who would have known that in Amsterdam the public executioner, although still subject to popular infamy, had become a rather well-paid public official. In the colonies, the infamous status of the executioner deepened: in Saint Domingue, for instance, he was always a slave condemned to die, who had been given the chance to live as a hangman. Stedman noted the “commiseration” of the executioner in one of the punishments he witnessed, and perhaps Coridon’s executioner also regarded him with sorrow.100

What then was Coridon’s legacy? Not Eva’s child, who was born of a color that indicated that Thoma was the father. But Samsam, one of his coconspirators, who a year later led a Maroon raid on a Commewijne plantation shouting, “The whites must know that [one of those] who killed Thoma still lives.”101