by Natalie Zemon Davis

In February 1792, David Nassy, secretary and associate treasurer to the Mahamad of the Portuguese Jewish Nation of Suriname, penned a letter of lament and supplication to the “Dignissimos Senhores” of that august body and to its Adjuntos, the council members of the Nation.1

He signed his letter David Nassy rather than David de Isaac Cohen Nassy, the name he was given at his birth in 1747 to Sarah Abigail Bueno de Mesquita and Isaac de Joseph Cohen Nassy, a descendant of early settlers of the colony. Before this, though, David had written his full name often enough, as, through the decades, he carried out the obligations of his many roles in the community: he followed his father for a term as sworn notary (jurator) of the Portuguese Jewish Nation; served as gabay, secretary, and one of the regents (parnasim) for the Mahamad; translated texts from Portuguese and Spanish into Dutch for the Suriname Court of Policy; ordered inventories to be made of his plantation and possessions; purchased medicines for his pharmacy,and contributed manuscripts in French and Dutch to the more general intellectual culture of the colony. Then, in January 1790, he went before the current jurator of the Nation and formally shortened his name to David Nassy: he claimed it was for the sake of simplicity— too many men had similar long names—but he also wanted to appear more modern.2

Jodensavanne, Suriname (Benoit, 1839)

Jodensavanne, Suriname (Benoit, 1839)

The tone of Nassy’s supplication to the Mahamad and Adjuntos was plaintive, but this did not mean that he could not look back from 1792 on a life of accomplishment and some fulfilled hopes—for himself, for the “benefit of the Nation and the glory of the Jewish name,” and for the literary life of Suriname, where, despite limitations, he and his fellow Jews enjoyed “a kind of Political Patrimony.”3

Nassy married his cousin Esther Abigail de Samuel Cohen Nassy in 1763, and four years later Esther gave birth to their daughter Sarah. Nassy’s purchase of the Tulpenberg coffee plantation on the Suriname River in 1770 had ended, partly through mismanagement, in financial disaster by 1773. (A fate suffered by other Suriname planters who had relied naively on easy credit arrangements offered from Amsterdam). But, thanks to bequests from his father Isaac, who died in 1774, and property brought to the marriage by his wife, David Nassy still owned land on creeks off the Suriname River, houses at Jodensavanne on the Suriname River and in the town of Paramaribo, and slaves. In 1777, he set up a partnership with Solomon Gomes Soares, “doctor and apothecary” at Jodensavanne: they would practice pharmacy together and Gomes Soares would instruct him in the art of healing. The partnership fared so well that by 1782, Nassy and his wife hired an agent in Paramaribo to acquire medicines for them. That same year, Esther’s jewelry case included diamond rings and gold bracelets.4

In the 1780s, Nassy was also able to celebrate the Portuguese Jewish Nation. The year 1785 was the hundredth anniversary of Beraha VeSalom (Blessing and Peace), the synagogue at Jodensavanne. By that time, a wooden synagogue had been built at Paramaribo for the Portuguese Jews (the synagogue for the Jews of the German Nation was nearby), but Beraha VeSalom was a splendid brick construction and the oldest religious building in the colony. David Nassy was impresario and director for the Anniversary Jubilee held in October 1785. Tableaux on themes of persecution, tolerance, and charity were presented to the Governor, the councilors of the Suriname courts, the militia officers and the Jewish dignitaries; songs were sung, Hebrew prayers recited, and poems declaimed. Then, Christians and Jews banqueted and danced the night away.5

At about this same time, Nassy began to agitate for the reform of the Ascamoth—the ordinances of the Jews of the Portuguese Nation— that had been last issued in 1754. His plea reflects the language and ideas of the European Enlightenment: “it is necessary to purge our ecclesiastical institutions of their errors, to uproot our old habits, and cut away our prejudices, the source of all our divisions.” Nassy won his case, and, with support from the Suriname government, submitted a revised Ascamoth that was approved in 1789. In fact, the new ordinances strengthened the hand of the parnasim against restive members of the congregation and the possible criticism of the rabbi, “who [was] not to preach about anything but morals in general.”6

In these same decades, David Nassy’s role also expanded in the wider cultural life of Suriname. The Portuguese Jews had been pioneers in the acquisition of books in European languages from Amsterdam, and Nassy’s own collection, inventoried in 1782, was perhaps the largest. His shelves contained approximately 450 volumes in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Latin, and Hebrew—a collection that included classics of the Enlightenment, European poetry, romance, and history, and medical and pharmacological texts. Collectors, both Jewish and Christian, later established a public library, which, according to Nassy’s perhaps exaggerated boast about his fellow settlers, “was filled with books on every subject, and yielded to no other library in all of America.”7

In 1774, the first printing press was set up in Suriname, and learned societies emerged alongside it. Nassy, unsurprisingly, took part in these societies; he read a paper on medicinal plants to the new Natural History Society, and another, on the meanings of the words roman (novel) and romance, to the new Society of Friends of Letters.8

The Portuguese Jews founded their own literary society as well, the Docendo Docemur (“we are taught by teaching”), and devoted many of their meetings, in 1786, to a French translation of Christian Wilhelm von Dohm’s recent plea for Jewish emancipation, Über die bürgerliche Verbesserung der Juden. Out of their discussions of this work came Nassy’s decision to write a book about the history, economy, government and cultural life of Suriname, which would give full and hitherto unacknowledged credit to the role of its Jews. A few years later the two-volume Essai historique sur la Colonie de Surinam (Historical Essay on Suriname) appeared. The work’s title page named the Regents of the Portuguese Jewish Nation as author, and gave its place and date of printing as Paramaribo, 1788. In fact, David Nassy was the author, (who wrote in his preferred literary language of French), and the book had been printed by the busy Amsterdam publisher Hendrik Gartman, who did not get the pages back to Suriname until the spring boats of 1789.9

Looking merely at this public record, we would be hard-pressed to understand the melancholy mood of David Nassy’s 1792 supplication to the Mahamad and Adjuntos. But there is more to the story. In November 1789, Nassy’s wife, Esther Abigail, died, leaving him with their only child, Sarah, who remained unmarried in 1792 at the age of twenty-four—an age when three-quarters of Portuguese Jewish women had already found a husbands and borne children.10 Sarah was mentally astute, as shown by commercial transactions, signed in a fine, clear hand, in which she was involved even as a teenager. But she seems to have faced some other difficulty. In detailing his unhappy lot to the Mahamad and Adjuntos, Nassy did not explicitly mention the death of his wife, but he did speak of the “well-known infirmity . . .of this poor daughter, to whom nature has assigned me all the care.”11

The main burden of Nassy’s complaint to the Mahamad and Adjuntos concerned calumnies against him, uttered by “a vile conspiracy” (“hua vila Cabala”), which were making it difficult for him to continue his many services to the Nation and were endangering his livelihood in Suriname. What was behind these intrigues? Possibly some men from established Portuguese Jewish families objected to Nassy’s restructuring of the Ascamoth. In any case, that Ascamoth, and Nassy as its framer, were the targets of strong criticism by the newer mulatto Jews, whose status as lesser members of the congregation of Portuguese Jews—mere congregaten, with special seating arrangements, rather than full jehidim—Nassy had maintained in the 1789 Ascamoth. But attacks from the congregaten may not have worried Nassy much: in 1791 he was writing against their claims to full ritual and ceremonial status, and he was fully backed in this by the parnasim.12

Instead, the “calumnies” and “conspiracy” that troubled Nassy were those provoked by his Essai historique. Fending off these criticisms, he reminded the Mahamad and Adjuntos how he had “courageously written a defense of our Nation” and made public “facts unknown to our own people and forgotten in the old papers of [our] Archives, [which] do honor to the Portuguese Jews of Suriname.”13 (Nassy might have added how much the book contributed to the general history of Suriname, including its economy and population, but he was here trying to persuade the parnasim and other worthies.) Possibly some members of the Nation itself had been put out by the way the Essai favored certain families—the Nassys, the Pintos, the de La Parras—and paid less attention to others. But it is sure that the directors of the Societeit van Surinam, which owned the colony, made objections from Amsterdam, and questions were raised in Paramaribo by its current governor, Wichers, even though Nassy had written of his fiscal and cultural policies with praise. Meanwhile, a faction among the Christian planters who had long been unhappy about the Jews’political role in the colony would have found much to disagree with in the Essai. Indeed, Nassy was later to write of his book that while English and French journalists had spoken of it “to advantage,” the Essai had been “disparaged” (“décrié”) in the colony.14

Faced with this “conspiracy,” Nassy told the Mahamad and Adjuntos he had no other choice but, with “tearful sentiments . . . shortly to leave my native land. . . to abandon my responsibility and care for the interests of the Nation and deprive myself of the company and affection of my worthy friends and protectors.” Reviewing the many services he had performed for the community over the years, Nassy requested that the Mahamad and Adjuntos grant him a threeyear leave of absence, or “furlough” (he used the Dutch word Verlof), reminding them that his salary as secretary to the community had been raised in 1789, and that in addition his salary covered his extra work as translator. It would be difficult to maintain himself and his “poor and helpless daughter” (“pobre e desvalida filha”) in foreign lands; the climate would be different, his health was fragile. Thus, he requested some funding for the three years of his leave, although the bulk of his salary would of course be going to his replacement as secretary. For the latter post, he nominated Abraham Bueno de Mesquita, current jurator of the community. Nassy described him as his friend and relative (Nassy’s mother was a Mesquita), and indeed, as a friend to most of the parnasim—a man of “zeal and integrity in his service to the Nation.”15

But Nassy had another request. Since 1774, he had had on rental and “under his authority” a young slave named Mattheus and his sister Sebele. Mattheus and Sebele were part of the estate of the late David Baruch Louzado, bequeathed to and administered by the Portuguese Jewish Nation. Mattheus had learned the art of carpentry, Nassy’s request went on, but, through some misfortune, around 1788 swollen spots began to appear on his body. Doubts were raised about whether his disease was contagious—Nassy himself believed that Mattheus had a skin condition particular to Africans and not leprosy—but the Mahamad and Adjuntos decided he could not be put up for public sale in 1790, when some other slaves from the Louzada estate were auctioned off. In fact, a government ordinance prohibited public sale in such circumstances.

Nassy asked that he be allowed to purchase Mattheus. The young man had shown such loyalty and goodness caring for the sick in Nassy’s house that Nassy believed he would be a great help to him as well in his “sad days . . . in foreign lands.” Since Nassy could never sell Mattheus publicly and was therefore taking a risk in purchasing him, he thought it fitting for the Mahamad and Adjuntos to sell him Mattheus at a reasonable price.16

How would Mattheus have regarded all this? We can track him down and perhaps provide some answers to this question through the Mahamad’s accounts of the Louzada estate. Mattheus was born about 1770 to Diana, slave of David Baruch Louzada, and an unknown black father, and lived with his mother, his older sister, Siberi, and another slave family in Louzada’s household. Louzada did not own a plantation, so Mattheus’s earliest memories would have been of the hills and fields of Jodensavanne. At Louzada’s death in 1774, the Mahamad rented Diana, Mattheus and Siberi not directly to David Nassy, but to his mother Sarah Abigail for ninety-one guilders a year. Because his father, Isaac Nassy, had just died, and David Nassy’s plantation had gone bankrupt and been sold the year before, David was thus an inappropriate lessor; he and his widowed mother probably set up household together in those years of financial trouble.17

Mattheus spent his boyhood in Jodensavanne, where David Nassy’s daughter Sarah, three years older than he, was growing up as well. The language used most frequently between slaves and their owners at that time was presumably Dju-tongo, the Portuguese-based creole spoken among slaves on the Jewish plantations of Suriname. Although Nassy himself considered creole tongues mere “jargon,” he probably taught Portuguese only to those few mulatto slaves in his household whom he “instructed in the Jewish religion.” In the 1770s, Mattheus would have known Nassy’s mulatto slaves Moses, Ishmael and Isaac, all of whom were circumcised after their birth and destined for manumission.18

In the 1780s, when Nassy’s relations with his creditors had eased up, he was able to establish his household once again on Green Street in Paramaribo. There Mattheus received his training as a carpenter and was rented out by Nassy (as were other slave carpenters) for building tasks in town. Mattheus became familiar with the town’s markets and varied population, including its free blacks and persons of color. Much outnumbered by the slaves in Paramaribo, free blacks and people of color plied trades of all kinds, peddled goods, and mounted balls attended by men and women dressed in fine silk and chintz. Sometimes they as well would own a slave or two, whom, at their deaths, they would manumit or bequeath to a relative. Mattheus would also have taken note of the Paramaribo prayer house of Darhe Jesarim (Way of Righteousness), the brotherhood of the free Jewish persons of color, whose status as an independent institution was soon to be of great concern to David Nassy and the Mahamad. Mattheus would have seen the slaves who accompanied their owners as they went about activities in town and who were dressed to do honor to their masters and mistresses. He himself, perhaps, carried an umbrella over the heads of David and Esther Nassy on their way to the Paramaribo synagogue of the Portuguese Nation and waited for them outside until the service was over.19

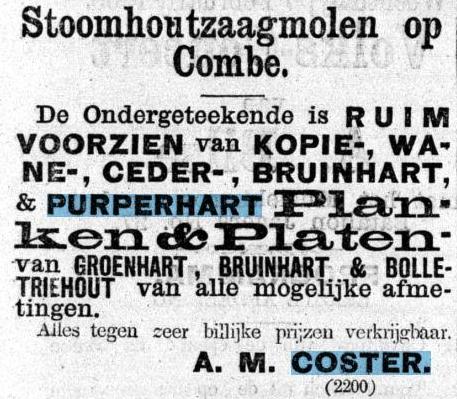

This period was also a time of loss for Mattheus. In 1783, the Mahamad announced in the Surinaamse Courant the sale of some slaves from the Louzada estate, and we can deduce that Mattheus’s mother was likely to have been among them, as David Nassy’s rental payments to the Mahamad for 1788 mention only Mattheus and his sister, now called Sebele (Sebele may be a version of Siberi, but perhaps Diana had another daughter).20

It was also in this year that the swollen spots cropped up on Mattheus’s body. Physicians and close observers of slave life in Suriname in the eighteenth century have described two serious illnesses of the skin especially affecting persons of African origin: yaws, and an incurable illness known in the Suriname Creole as “boisi” or “boassi,” which was compared variously to leprosy and elephantiasis.21 Nassy’s denial to the Mahamad that Mattheus was afflicted with “boassi” (in his request to purchase him) would lead us to believe that Mattheus’s lesions evidently suggested the disease, and we can imagine Mattheus’s anxious conversations with his fellow slaves about remedies and rituals for healing. Nassy also must have done his best, and he may even have used herbal baths learned from African healers in his attempts to cure Mattheus, for, despite his contempt for their “frightful ceremonies,” Nassy admired the healers’ knowledge of local medicinal plants.22 In any case, despite Mattheus’s skin condition, he was very much alive and ready for travel four years later.

The Mahamad and the Adjuntos granted both of David Nassy’s requests, though Mesquita’s replacement salary and Nassy’s leave benefit may have been less than requested. Interestingly enough, Mattheus is recorded in the accounts as sold to Sarah Nassy rather than to David, similar to how he had been, previously, leased to her grandmother. In the next months, father and daughter were busy with preparations for what they now specified as a trip to North America: they settled with creditors and gave power of attorney to Mordechai de La Parra to represent them in their absence.23 And they arranged for passage on a spring boat from Paramaribo to Philadelphia.

Why Philadelphia? News from North America was printed regularly in the Surinaamse Courant: Nassy could read there of the successful revolution of the English colonies against their mother country and of the debates about the new constitution in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. News also came to Suriname through travellers and letters. The Moravian missionaries in Suriname, for example, had frequent exchanges with their Brethren in Pennsylvania, and Jews had connections as well. In 1784, Eliazer Cohen, a schoolmaster in Philadelphia, set up two German Jews in Suriname to be his agents for the estate of his father Eliazer David Cohen, who had lived and died in Suriname. By the early 1790s, Eliazer Abraham Cohen—possibly the schoolmaster himself—was cantor and then rabbi at the German Jewish synagogue in Paramaribo.24 In Philadelphia, Nassy could expect a political and intellectual atmosphere suited to his Enlightenment curiosity and his constant interest in projects for betterment, a Jewish community in which he and his daughter could make a start, and a medical establishment that would perhaps welcome him.

Nassy must have, in some ways, prepared Mattheus for the trip. By now, since Mattheus had served not only as a carpenter but also as a close personal servant in the household, Nassy may well have taught him Portuguese or, perhaps, French, Nassy’s preferred second language. In any case, both master and slave had a language challenge ahead of them, for neither knew English beyond those words embedded in the Suriname creole. Possibly Mattheus got news through the slave and free-black networks in Paramaribo of the flourishing movement in Philadelphia for the abolition of slavery, but David Nassy would have been loath to broach the subject with his slave even if he had had information about it. No friend of abolition, Nassy went no further in his views than the most enlightened of the Suriname planters and preachers: slavery was an acceptable institution but must be conducted with humanity and beneficence, without (as Nassy wrote in the 1789 Essai) the “rage that [some] Whites conceive against the Blacks,” and without “the cruel tortures they make them suffer.”25

On 21 April 1792, David Nassy, his daughter Sarah Nassy, “and her slaves Mattheus and Amina,” left Paramaribo on the American ship Active for Philadelphia. Amina was a little girl of about ten, a mulatto, and evidently important to Sarah.26

David Nassy’s first stops that we can trace in Philadelphia were the Mikveh Israel synagogue and the court for manumission. Built in 1782, the Mikveh Israel synagogue drew Jewish families of varied geographical origin, but its ritual followed the Sephardic liturgical practice familiar to Nassy. By the Jewish New Year of 5553 (September 1792), he had paid his synagogue dues for the entire past year of 5552, even though he had arrived in Philadelphia only in the spring.27

Among the worshippers at Mikveh Israel Nassy soon met the merchant and entrepreneur Solomon Marache. This was an appealing connection for Nassy because, among other reasons, the two men could chat in Dutch: Marache had been born in Curaçao and lived there until, as a teenager in 1749, he was taken to New York by his widowed mother to learn his trade. Marache had since flourished in Philadelphia and become an important figure in the congregation Mikveh Israel already in the years before the synagogue was built. After 1787, when he took a widowed non-Jewish woman as his second wife, Marache no longer served as treasurer to the congregation, but continued to attend services. As Nassy himself described it: “The Maraches . . . and [men of] several other families [are] lawfully married to Christian women who go to their own churches, the men going to their synagogues, and who, when together, frequent the best society.”28

Through his second wife, Solomon Marache was in fact in contact with people who believed in the abolition of slavery. Since the 1780s, a number of worshippers at Mikveh Israel had been manumitting their slaves, especially encouraged to do so by two of their brethren, Solomon Bush and Solomon Marache. Bush, a member of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1789, was the only Jew to be associated with the organization in its early days. He married a Quaker woman in 1791, and, when he died in 1795, Bush at his own earlier request was buried in the Friends cemetery, where he would lie among those who had founded the Society. Solomon Marache’s second wife—born Mary Smith—had a Quaker mother and cousins, and her brothers and maternal cousin George Aston, who was both an officer of the society and especially close to Mary, were members of the Abolition Society.29

On 9 August 1792, Solomon Marache accompanied David Nassy together with his daughter Sarah, Mattheus and Amina to the court chambers of Philadelphia. There David Nassy “late of Surinam now of the City of Philadelphia, Doctor of Physick” manumitted and set free “his Negroe man Matheus aged about twenty two Years.” Nassy went on to “reserve his servitude,” that is, to indenture Mattheus for seven years. At this time he also changed Amina’s name to Mina—“my Mulatto Girl named Mina aged about ten years”—and after freeing her reserved her servitude as well, to himself or to those he would assign, for eighteen years.30 In this ungenerous manumission, Nassy was following Pennsylvania’s Gradual Emancipation Act of 1780, which provided that any personal slave brought into Pennsylvania by a new resident must be freed at the end of six months, but within that period of six months, the master could indenture a slave until the age of twenty-eight (the case of Mina) or for seven years if the slave was not a minor (the case of Mattheus).31

Solomon Marache must have tried to persuade David Nassy to become more open to the importance of abolition. Also, Nassy is known to have had conversations with other Philadelphia opponents of slavery, such as the celebrated physician Benjamin Rush, a major figure in the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, to whom Nassy presented a copy of his Essai historique in June 1793. But Nassy’s three years in Philadelphia seem to have moved his thoughts little on this score. Writing in February 1795 about “the means of improving the colony of Suriname” and referring undoubtedly to recent events in Saint Domingue, he commented that:

for Blacks who have not come to a certain level of civilization, the ideas of liberty and equality throw them into a state of drunkenness (“espèce d’ivresse”), which does not pass until they have destroyed everything . . . Until freedom has been preceded by enlightenment . . . it will be the most disastrous present one can give to Blacks.

Nassy recalled manumitted slaves in Suriname who, he claimed, “had of their own volition returned to the discipline of their former masters to be fed, clothed, and cared for in their maladies.”32 Nassy may also have been justifying here the seven years of service he was in the midst of requiring from Mattheus.

Much went on in the medical, pharmaceutical, intellectual, and political life of David Nassy during his “furlough” in Philadelphia which we cannot consider here. Nor can we here speculate on the discoveries made during those years by Sarah Nassy and her mulatto servant Mina, and the interesting possibility that Sarah took Mina with her to the women’s section of Mikveh Israel.

But, we do wish to imagine some of the experiences of the indentured servant Mattheus. Philadelphia was a hub of black— especially free black—life in the new United States. In contrast to Paramaribo, the free black population of Philadelphia (somewhat more than 1800 when Mattheus arrived there) outnumbered the slave population more than six to one. If David Nassy arranged for Mattheus to work as a carpenter in Philadelphia, he would have come into direct contact with this world. Surely he was aware of the Free African Society, a benevolent association founded in 1787 by two remarkable ex-slaves, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen (Jones went on to establish the African Episcopal Church, where the first sermon was delivered in July 1794, while Allen set up a place of worship for black Methodists the same year). Rather than accepting a pattern of life in which manumitted slaves went on to acquire slaves of their own, as in Suriname, Jones and Allen entreated “the people of color .. . favored with freedom…to consider the obligations we lay under to help forward the cause of freedom, we who know how bitter the cup is of which the slave hath to drink, O how ought we to feel for those who yet remain in bondage?”33 Part of a Jewish household, Mattheus would probably not have attended such services, but he surely heard word of the pleas of Jones and Allen.

Mattheus may well have been involved, however, in the assistance provided by Philadelphia blacks during the devastating yellow fever epidemic of August through November 1793. Benjamin Rush believed—mistakenly as it turned out, but perhaps conveniently— that blacks were immune to the illness; thus they were called upon, or volunteered themselves, to care for the sick and bury the dead. Nassy, whose wise and moderate methods of treatment managed to keep most of his patients alive, did not subscribe to Rush’s view. He speculated, rather, that “foreigners,” that is, those not native to Philadelphia, were less susceptible to the epidemic because their “temperaments” and “constitution” were linked to the climate and air of the places in which they had grown up; those whose constitution was linked to the climate and air of Philadelphia were more likely to be infected.34 Thus, Mattheus would have served at Nassy’s right hand, or in attendance to others, during the epidemic not as a black man, but as a “foreigner” like the master to whom he was indentured.

Finally, Mattheus met with adventures and conversations of a less risky sort as well. Nassy had early made contact with Peter Legaux, a Frenchman from Lorraine, who was trying to establish viticulture in Pennsylvania. Legaux gave a copy of Nassy’s Essai historique to the American Philosophical Society in the autumn of 1792, and not long after presented Nassy himself; but, of more import to Mattheus, Legaux introduced Nassy to the French aviationist Jean Pierre Blanchard, who had come to Philadelphia for North America’s first aerial voyage. On 9 January 1793, when Blanchard prepared to rise in his hydrogen-filled gas balloon, Pierre Legaux and David Nassy were holding the restraining ropes. President George Washington had shaken Blanchard’s hand before he boarded his basket, but the servant Mattheus was surely nearby, watching the balloon rise and drift away on its successful fifteen mile flight.35

Legaux had spent some years in Saint Domingue before coming to Philadelphia in 1785, but Nassy also had connections with émigrés who had witnessed and fled the later great revolts on that island. Solomon Moline came to Philadelphia with his family and slaves not long after the first Saint-Domingue slave uprising in 1791; Nassy would have seen him at Mikveh Israel, where Moline was close to Benjamin Nones, a leading figure in the congregation. Indeed, Nones accompanied Moline to court when he manumitted his slaves without requiring further servitude.36 Later, in August 1793, as the end of slavery in Saint Domingue seemed assured, the physician Jean Devèze arrived with his family and slaves from Cap de François with tales of a recent bloody battle, of continuing uprisings, destruction, and slaughter. In Philadelphia, Devèze immediately plunged into the treatment of those stricken by the epidemic, and, with a medical approach very similar to that of Nassy, they became friends. Reports from Moline and Devèze must have been among the sources fuelling Nassy’s image of the “state of drunkenness,” into which he believed blacks were thrown when they had not yet been “enlightened” by instruction.37

For Mattheus, however, conversations with the slaves that Moline and Devèze had brought with them—soon to become ex-slaves by Pennsylvania law—would have had a different tenor.38 They would have found a way to communicate—either in French if they knew it— or in a pidgin constructed from their differing creole languages. From such exchange Mattheus could hear of a hoped-for republic, where blacks and people of color would be free citizens administering their own polity, in contrast with the societies of free Maroons he knew of in Suriname, living in tribal clans with respected kings, and with the free black communities in Philadelphia, enterprising and aspiring, but still subaltern in a society dominated by white folks.39

In the spring of 1795, the three years of David Nassy’s furlough were up, and he sat down to write a letter in English to the merchant house of Brown, Benson and Ives in Providence, Rhode Island asking for passage on one of their boats to Suriname. His “family of four” would make their way by land to Providence, he wrote, making clear that Mina and Mattheus were still part of the picture.40 We may wonder why Mattheus did not run away rather than return with his master to Suriname. His previous illness and residual skin condition, which surely made Mattheus dependent on the physician Nassy—or at least less able to initiate new permanent relations in a foreign land—may have been a factor. Also, in Suriname, Mattheus had his sister Sebele and other kin. Furthermore, Nassy’s 1792 letter to the Mahamad and Adjuntos suggested his paternalistic attachment to the young man.

The “family” left sometime after 19 June 1795, the date when Nassy bade farewell to the American Philosophical Society. On the way back, Nassy decided to have the four of them disembark at the Danish island of Saint Thomas, where he visited its growing Jewish community and had himself examined by a learned Danish royal physician who was there on a brief visit. By January 1796 he was back in Paramaribo, recounting his adventures to the Mahamad of the Portuguese Jewish Nation; a few months later he was signing documents once again as Secretary to the community.41

If his furlough in Philadelphia had not changed Nassy’s mind about the legitimacy of slavery, it had deepened his commitment to educational reform. By the fall of 1796 he had published a new proposal for a college in Suriname and was far advanced in raising money for it: the school would be dedicated to letters and sciences, liberal arts and crafts and trades suitable for “American lands in the tropics.” It would be for boys only, but for boys both rich and poor (funding would be provided for the latter), and for Jews and Christians both. The pupils would, of course, be free in status (the only slaves listed in his prospectus are those rented for kitchen, washing, and maintenance duty), but there is no mention in Nassy’s prospectus of a color bar. I think we can see here the influence of what he had observed in Philadelphia: the intensive social and cultural exchange between Jews and Christians and the energetic efforts of free people of African descent to achieve the “enlightenment” that he thought essential to the “social man” and “civilization.”42

As for Mattheus, his contracted service to Nassy was to last until the spring of 1799. We may wonder whether Nassy taught him to read and write Portuguese and/or Dutch in those years, if he had not already done so. There is no sign of him, however, among the congregaten of the Portuguese Jewish Nation in the late 1790s or the early years of the nineteenth century, although he may well have remained associated with the blacks and people of color that he had known in the Jewish households in which he had grown up. In 1799, now twenty-nine years of age, Mattheus was free to put up his own wooden sign as a carpenter, with a surname added on. Because manumitted slaves in Suriname took the last name of their former master or mistress preceded by “de” or “van, Mattheus’s surname would almost certainly have been de Nassy or van Nassy.”43 We can imagine Mattheus in one of the small Paramaribo shops, recounting to his neighbors stories of Blanchard’s balloon, the frightening epidemic, and the Free African Society. And we can find it likely that when he needed help in his carpentry, he hired a young lad for wages rather than acquiring a slave. From Philadelphia, he could have carried with him, if not the words, then the spirit of Absalom Jones and Richard Allen: “to consider the obligations we l[ie] under to help forward the cause of freedom, we who know how bitter the cup is of which the slave hath to drink.”44

David Nassy’s “Furlough” and the Slave Mattheus

1. Nationaal Archief, The Hague, the Netherlands (henceforth NAN), Archief der

Nederlands-Portugees-Israelitische Gemeente in Suriname (henceforth ANPIG) 87,

947–954 (American Jewish Archives microfilm [henceforth AJAmf] 67n).

2. NAN, ANPIG 799, 8 January 1790 (AJAmf 67c). Biographical material on David

Nassy can be found in R. Bijlsma, “David de Is. C. Nassy, Author of the Essai

Historique sur Surinam,” in The Jewish Nation in Suriname, ed. Ruobert Cohen

(Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1982), 65–73 and Robert Cohen, Jews in Another

Environment. Surinam in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century (Leiden and New

York: E. J. Brill, 1991). I will be treating David Nassy further in my forthcoming

study Braided Histories: Slavery and Sociability in Colonial Suriname.

3. NAN, ANPIG 87, 754 (AJAmf 67n). [David Nassy], Essai Historique sur la Colonie

de Surinam, 2 vols. (Paramaribo, 1788 [sic for Amsterdam: Hendrik Gartman, 1789]),

1: xv.

4. NAN, Suriname Oud Notarieel Archief (henceforth SONA), 788, 1r–4v; SONA

789, 29–30, 41–42, 81–84 ; SONA 791, no. 8, 22 March 1786 (AJAmf 67b).

5. NAN, ANPIG 155 (AJAmf 179). Beschryving van de Plechtigheden nevens de

hofdichten en gebeden, uitgesproken op het eerste Jubelfeest van de Synagoge der

Portugeesche Joodshe Gemeente, op de Savane in de colonie Suriname, genaamd

Zegen en Vrede (Amsterdam: H. Willem and C. Dronsberg, 1785).

6. [Nassy], 1: 176; Cohen, Jews, 146–153.

7. Cohen, Jews, 181–239. [Nassy], 2: 79.

8. [Nassy], 1: 165–166, 2:77–80. Michiel van Kempen, Een Geschiedenis van de

Surinaamse Literatuur, 2 vols. (Breda: Uitgeverij De Geus, 2003), 1: 251–283.

9. [Nassy], 1: v-xxiv. Bijlsma, 70. NAN, ANPIG 156 (AJAmf 179).

10. NAN, ANPIG 420 (Registrar dos Sepultados), 45r. Robert Cohen, “Patterns of

Marriage and Remarriage among the Sephardi Jews of Surinam, 1788–1818,” Jewish

Nation, 92, 99. Sarah Cohen Nassy died unmarried in 1803 at age thirty-six (ANPIG

20, 5564 Kislev 25; 10 December 1803).

11. NAN, ANPIG 257, session of 27 June 1786; ANPIG 179, receipt of 30 November

1787 (AJAmf 183); ANPIG 87, p. 949 (AJAmf 67n).

12. NAN, ANPIG 87, pp.753, 948 (AJAmf 67n). Cohen, Jews, 156–172. See further

on the relation between colonial Jewish communities and converts of color in the

important book by Jonathan Schorsch, Jews and Blacks in the Early Modern World

(Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2004), chap. 9.

13. NAN, ANPIG 87, 948 (AJAmf 67n).

14. [Nassy], 1: 167, 179–82, 103–13; 2: 22, 78–9. Bijlsma, 70. David Nassy, Lettre-

Politico-Theologico-Morale sur les Juifs (Paramaribo: A. Soulage Jr., 1799), lxxvi.

15. NAN, ANPIG 87, pp. 949–952 (AJAmf 67n). Nassy’s salary as secretary for the

community was listed as 1600 guilders in the budget for 1792 (NAN, ANPIG 194;

[AJAmf 184]). Schiltkamp, “Jewish Jurators in Surinam,” in Jewish Nation, 62.

16. NAN, ANPIG 87, 952–953 (AJAmf 67n). J. A. Schiltkamp and J.Th. de Smidt,

Plakaten, Ordonnantiën en andere Wetten, uitgevaardigd in Suriname, 2 vols.

(Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1973), 2: 971–972, no. 811 (ordinance of 10 February

1780).

17. NAN, ANPIG 167, Boedel David B. Louzada (AJAmf 149). No plantation is

listed under the Louzada name in any of the eighteenth-century Suriname maps,

which cover all the rivers and creeks. David Hisquiau Baruch Louzada, who was born

at Jodensavanne in 1750 and who became hazzan of the synagogue there in 1777, was

surely a relative of David Baruch Louzada. The younger man, David Hisquiau, also

had associations with David Nassy; we find him, for instance, as one of the appraisers

of Nassy’s estate in 1782. (Z. Loker and Robert Cohen, “An Eighteenth-Century

Prayer of the Jews of Surinam,” Jewish Nation, 75–77; NAN, SONA 789, 41, 71

[AJAmf 67b]). But the older David Baruch Louzada willed either his entire estate

or else just the slaves from his estate to the Portuguese Jewish community, which

collected the payments for the rental of the slaves.

18. [Nassy], Essai, 2:25. NAN, Raad van Politie, Requeten 417, 64–65. Norval

Smith, “The history of the Surinamese creoles II: Origin and differentiation,” in Atlas

of the Languages of Suriname, ed. Eithene B. Carlin and Jacques Arends (Leiden:

KITLV Press, 2002), 139–142. I have also treated the language spoken on the Jewish

plantations in Natalie Zemon Davis, “Creole Languages and their Uses: The Example

of Colonial Suriname,” Historical Research 82 (2009): 268–284. Jewish converts in

Suriname are discussed in Aviva Ben-Ur, “A Matriarchal Matter: Slavery, Conversion,

and Upward Mobility in Suriname’s Jewish Community,” in Atlantic Diasporas:

Jews, Conversos and Crypto-Jews in the Age of Mercantilism, 1500–1800, ed.

Richard Kagan and Philip D. Morgan (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University

Press, 2009).

19. Public Record Office, London, WO 1/146, f. 1v; [Nassy], Essai, 2: 38–39. Cohen,

Jews, 164–166. P. J. Benoit, Reis door Suriname (Zutphen: De Walburg Pers, 1980),

figs. 12–14, 16, 18–19, 24–25.

20. De Weekelyksche Woendaagsche Surinaamse Courant (1 April 1783):

announcement by the Regents of the Portuguese Jewish Nation of the sale of a group

of slaves from the estate of the late David Baruk Lousada [sic]. NAN, ANPIG 190

(AJAmf 184) Conta e Descargo do Boedel de David Baruch Louzada, 1788: David

de Isaac Cohen Nassy pays for the rental of Mattheus, Sebelle and Dagon. Dagon first

appears on a 1784 account as rented out to Joseph Cohen Nassy, who had leased the

other family in the Louzada estate (NAN, ANPIG 167, Boedel David B. Louzada,

[AJAmf 67n]). Four years later he was leased to David Nassy.

21. Philippe Fermin, Traité des maladies les plus fréquentes à Suriname et des

remèdes les plus propres à les guérir (Maestricht: Jacques Lekens, 1764), chaps. 17–

18; Fermin practiced as a physician in Suriname from 1754–1762. Bertrand Bajon,

Mémoires pour server à l’histoire de Cayenne et de la Guiane Françoise, 2 vols.

(Paris: Grangé, 1777–1778), vol. 1, memoirs 8–9. Anthony Blom, Verhandeling van

den landbouw in de Colonie Suriname (Amsterdam: J. W. Smit, 1787), 339–342.

22. [Nassy], Essai, 2: 64–69.

23. NAN, SONA 799, 2 April 1792, 12 April 1792 (AJAmf 67c); NAN, ANPIG 196,

Boedel David B. Louzada (1794); ANPIG 197 (1795): Abraham Benito da Mesquita,

secretary at 500£ per year (AJAmf 185).

24. NAN, SONA 737, 530–31 (May 1784). AJA, ms. 13500 (23 December 1794).

25. [Nassy], Essai, 1: 97.

26. NAN, Societeit van Suriname 210, Journal, 1076.

27. Mikveh Israel Archives, Financial Records (1792), 28 September 1792 [12

Tishrei 5553], received from David Nassy payment in full for 5552. On the Jews of

Philadelphia, see Edwin Wolf and Maxwell Whiteman, The History of the Jews of

Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the Age of Jackson (Philadelphia: The Jewish

Publication Society, 1975).

28. On Solomon Marache, see Mikveh Israel Archives, Minute Book no. 1, p. 26;

Wolf and Whitemen, 61–62, 99, 110, 121–122, 146, 166, 175, 222–224, 431 n. 63.

Nassy, Lettre, 43.

29. Wolf and Whiteman, 190–192; Full text of “Centennial anniversary of the

Pennsylvania Society, for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery,” accessed on 22

February 2009 at http://www.archive.org/stream/centennialannive00penn/. Frances J.

Dallett, “Family of Mrs. Robert Smith: A Commentary on Genealogy of Esther Jones,”

Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine 33, no. 4 (1984): 307–324; Mary Smith Holton

Marache was the daughter of the Quaker Esther Jones Smith, and all her relatives on

the Jones side were Friends. Her cousin, the abolitionist George Aston, was close to

her and to the children she had in her second marriage with Marache.

30. Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Manumission Book of the Pennsylvania

Society for the Abolition of Slavery, Book A, ff. 134–135.

31. Gary B. Nash, Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black

Community, 1720–1840 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 60–62.

32. Wolf and Whiteman, 200. David Nassy, Mémoire sur les Moyens d’Ameliorer la

Colonie de Suriname (1795), 23–25, NAN, Eerste Afdeling Aanwinsten 1935, Inv.

33. Nash, 98–137. Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, “To the People of Colour,” in A

Narrative of the proceedings of the Black People during the Late Awful Calamity in

the Year 1793 (Philadelphia: William Woodward, 1794), 26–27.

34. Mathew Carey, A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in

Philadelphia, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1793), 76–77; Jones and Allen’s

publication is a response to Carey. Nash, 121–125. David Nassy, Observations sur la

Cause, la Nature et le Traitement de la Maladie Epidémique, Qui Règne à Philadelphie

(Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1793), 34–40. Wolf and Whiteman, 193–194.

35. Early Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society for the Promotion of

Useful Knowledge (Philadelphia: McCalla and Stavely, 1884), 207, 212. Background

note to and description of Peter Legaux’s Journal of the Vine Company of Pennsylvania,

manuscript in the American Philosophical Society Library, Accessed on 22 February

2009 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/library/mole/l/legauxvine.htm. On Jean Pierre

Blanchard’s aerial voyage from Philadelphia: http://www.historynet.com/jean-pierreblanchard-

made-first-us-aerial-voyage-in-1793.htm accessed on 22 February 2009.

36. Wolf and Whiteman, 191. They give Moline’s arrival date as 1793, but he is

already listed along with Benjamin Nones among those Philadelphians subscribing to

a turnpike road between Philadelphia and Lancaster in June of 1792 (Charles I. Landis,

The First Long Turnpike in the United States [Lancaster, Pa., 1917], 136). Moline’s

decision not to indenture his manumitted slaves may have been made from conviction

or simply from his having passed the six-month deadline for such an arrangement.

37. Jean Devèze, Recherches et Observations, Sur les Causes et les Effets de la

Maladie Epidémique qui a régné à Philadelphie [printed in French and English

translation] (Philadelphia: Parent, 1794), 2–3. Nassy mentions their friendship during

the epidemic in his Observations, 44.

38. On the influx of about 500 slaves from Saint Domingue and their manumission in

the years 1793–1796, see Nash, 141–142.

39. For the model developed in the French colonies in the wake of the revolution,

see Laurent Dubois, A Colony of Citizens: Revolution and Slave Emancipation in

the French Caribbean, 1787–1804 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

2004). For the model of freedom in the Maroon communities of Suriname, see Richard

Price, Alibi’s World (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990).

40. John Carter Brown Library, Providence, Rhode Island, Brown Papers (1795), 26

April 1795.

41. Early Proceedings, 232. Bijlsma, 71. Judah M. Cohen, Through the Sands of Time:

A History of the Jewish Community of St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands (Hanover,

NH: Brandeis University Press, 2004), 14–16. NAN, ANPIG 198, 4, 9 August 1796

(AJAmf 185).

42. David Nassy, Programma de Huma Caza d’Educaçao, ou Seminario de Criaturas

na Savana de Judeus [trilingual text in Portuguese, Dutch, and French] (Paramaribo:

A. Soulage, Jr., 1796).

43. Among examples of Jewish congregaten who had once belonged to a Nassy:

Joseph de David Cohen Nassy, Simcha de Jacob Nassy. An example from the

Reformed Church in 1787: Vrije Janiba van Adjuba van Nassy (Januba was the

daughter of Adjuba, who had been manumitted earlier by David Nassy). For an image

of such shops, see Benoit, fig. 32.

44. Jones and Allen, 26–27.

***

This essay was originally published in: Pamela S. Nadell, Jonathan D. Sarna and Lance J. Sussman, eds., New Essays in American Jewish History: Commemorating the Sixtieth Anniversary of the Founding of the American Jewish Archives (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 2010).

Home – American Jewish Archives

Click to access 2010_62_01_00.pdf

It was placed on this website with the kind permission of Natalie Zemon Davis and Dana Herman, Ph.D. Managing Editor & Academic Associate, The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives.

Natalie Zemon Davis is a Canadian/American professor of history at the University of Toronto in Canada. Davis is regarded as one of the greatest living historians and has written a large number of books and articles. She has also written a number of articles about Suriname. Buku – Bibliotheca Surinamica is very honoured to host this essay by Natalie Zemon Davis.

For questions and comments please mail us at: surinamica@gmail.com

Portuguese Sefardic synagogue Paramaribo

Begraafplaats Jodensavanne (1 maart 2022)

Begraafplaats Jodensavanne (1 maart 2022)